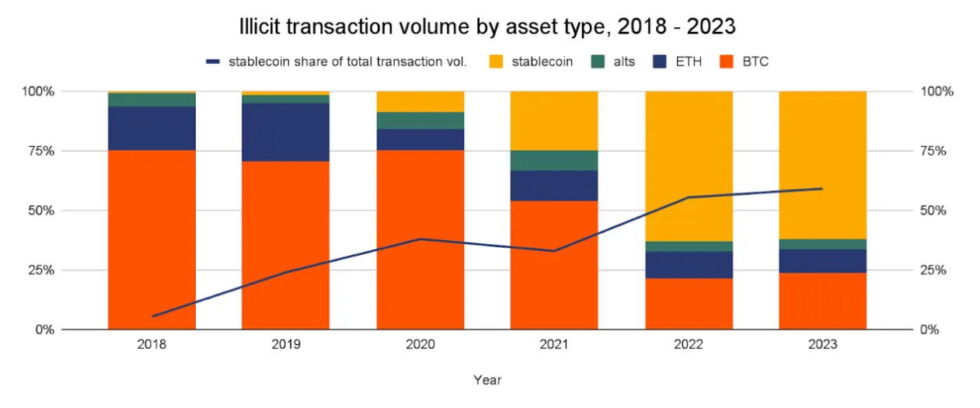

Stablecoins, cryptocurrencies pegged to a stable value like the US dollar, were created with the promise of bringing the frictionless, border-crossing fluidity of bitcoin to a form of digital money with far less volatility. That combination has proved to be wildly popular, rocketing the total value of stablecoin transactions since 2022 past even that of Bitcoin itself.

It turns out, however, that as stablecoins have become popular among legitimate users over the past two years, they were even more popular among a different kind of user: those exploiting them for billions of dollars of international sanctions evasion and scams.

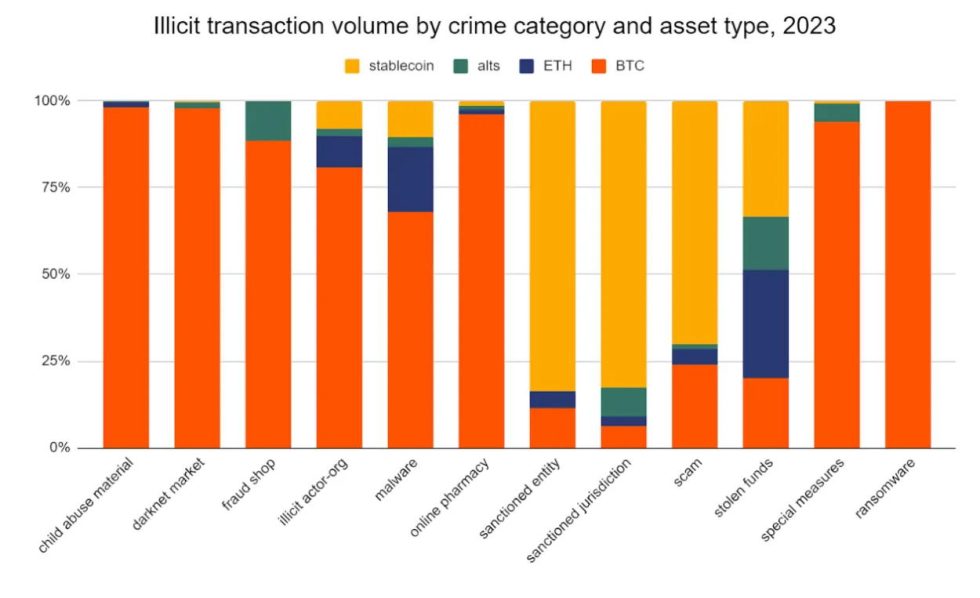

As part of its annual crime report, cryptocurrency-tracing firm Chainalysis today released new numbers on the disproportionate use of stablecoins for both of those massive categories of illicit crypto transactions over the last year. By analyzing blockchains, Chainalysis determined that stablecoins were used in fully 70 percent of crypto scam transactions in 2023, 83 percent of crypto payments to sanctioned countries like Iran and Russia, and 84 percent of crypto payments to specifically sanctioned individuals and companies. Those numbers far outstrip stablecoins’ growing overall use—including for legitimate purposes—which accounted for 59 percent of all cryptocurrency transaction volume in 2023.

In total, Chainalysis measured $40 billion in illicit stablecoin transactions in 2022 and 2023 combined. The largest single category of that stablecoin-enabled crime was sanctions evasion. In fact, across all cryptocurrencies, sanctions evasion accounted for more than half of the $24.2 billion in criminal transactions Chainalysis observed in 2023, with stablecoins representing the vast majority of those transactions.

The attraction of stablecoins for both sanctioned people and countries, argues Andrew Fierman, Chainalysis’ head of sanctions strategy, is that it allows targets of sanctions to circumvent any attempt to deny them a stable currency like the US dollar. “Whether it’s an individual located in Iran or a bad guy trying to launder money—either way, there’s a benefit to the stability of the US dollar that people are looking to obtain,” Fierman says. “If you’re in a jurisdiction where you don’t have access to the US dollar due to sanctions, stablecoins become an interesting play.”

As examples, Fierman points to Nobitex, the largest cryptocurrency exchange operating in the sanctioned country of Iran, as well as Garantex, a notorious exchange based in Russia that has been specifically sanctioned for its widespread criminal use. Stablecoin usage on Nobitex outstrips bitcoin by a 9:1 ratio, and on Garantex by a 5:1 ratio, Chainalysis found. That’s a stark difference from the roughly 1:1 ratio between stablecoins and bitcoins on a few nonsanctioned mainstream exchanges that Chainalysis checked for comparison.

Chainalysis concedes that the analysis in its report excludes some cryptocurrencies like Monero and Zcash that are designed to be harder or impossible to trace with blockchain analysis. It also says it based its numbers on the type of cryptocurrency sent directly to an illicit actor, which may leave out other currencies used in money laundering processes that repeatedly swap one type of cryptocurrency for another to make tracing more difficult.

Chainalysis’ findings come on the heels of another report released earlier this week by United Nations researchers on the outsize role of stablecoins in illegal gambling and scam operations across East and Southeast Asia. While Chainalysis declined to break out the value of any particular stablecoin in its findings, the UN report singles out Tether, the most popular stablecoin. The report describes Tether sent through the TRON blockchain-based payment network as the “preferred choice for regional cyberfraud operations and money launderers alike due to its stability and the ease, anonymity, and low fees of its transactions.”

“Pig butchering” scams—cons in which scammers typically trick users into sending funds into fraudulent investments—consistently use Tether as the means of bilking victims, says Erin West, a deputy district attorney for California’s Santa Clara County and a member of the REACT High Tech Task Force, who has long focused on crypto crime. “It’s always, always, always Tether. I’ve never heard of pig butchering that isn’t Tether,” says West. “These scammers can’t risk the volatility of any of the other coins like bitcoin or ether. All they want is to move assets from the victims’ hands to their own in the cheapest, easiest way possible.”

West says that the high proportion of stablecoin use in sanctions evasion also represents a disturbing trend, given that it undermines a system meant to hold specific countries, individuals, and companies accountable for criminal behavior and violations of international law. “It’s so dangerous,” West says. “It enables them to have access to the very units of currency that we’re trying to prevent them from accessing. This is exactly what sanctions are meant to stop, and they’re able to bypass it.”

When WIRED reached out to Tether Holdings—the company that issues the stablecoin that shares its name—it responded in a statement following publication of this article that “Tether proactively collaborates with global law enforcement agencies to identify and prevent illicit use of” its cryptocurrency, adding that its “commitment to the highest standards of compliance is evident in our efforts to eliminate various forms of criminal activity.”

Tether argued further that it has contributed to freezing the assets of users involved in scams or found to be violating the US Treasury’s sanctions lists, and noted that all of its transactions, like many cryptocurrencies, can be publicly observed on blockchains—in other words, the observability that made Chainalysis’ report possible. “Between our active and direct engagement with law enforcement and leveraging the transparent nature of blockchain transactions, individuals attempting to conceal their illicit financial activities face significant risks, as every transaction can be easily traced,” the company’s statement reads.

Tether Holdings has more flatly denied other reports of Tether’s use in crime and sanctions evasion. It wrote that an October Wall Street Journal article on the subject was based on “highly erroneous interpretations of data”—though in that case, the company pointed to Chainalysis findings as a more accurate accounting. “There is simply no evidence that Tether has violated Sanctions laws or the Bank Secrecy Act through inadequate customer due diligence or screening practices,” Tether Holdings wrote in an October 26 blog post addressing the WSJ article.

In contrast to most cryptocurrencies, Tether does have the capability to freeze user funds, and it said in the October blog post that since its launch in 2014, it had frozen $835 million in funds deemed to be tied to illicit activities. “Tether’s ethos revolves around transparency, compliance, and proactive collaboration with relevant authorities worldwide,” the company wrote.

Chainalysis’ Fierman says that Tether’s efforts to freeze criminal funds are having an impact, and more enforcement could help end stablecoins’ exploitation by criminals. “Just as we’ve seen with compliant exchanges dominating more and more of total transaction volumes, illicit activity gets pushed to the fringes,” Fierman says.

Despite Tether’s ability to freeze funds, Chainalysis’ data suggests that illicit use of stablecoins has so far dwarfed those seizures. West, the prosecutor, notes that most Tether associated with crime is cashed out for another currency long before anyone identifies it. That means Tether hasn’t yet come close to solving the underlying problem.

“I applaud it. I’m all for it,” West says of Tether’s efforts to freeze criminal assets. “But when we’re talking about billions and billions of dollars in assets moving, I just think this is one piece of one piece of the puzzle. There are so many more pieces. And the bad actors are so far ahead of us.”

This story originally appeared on wired.com.