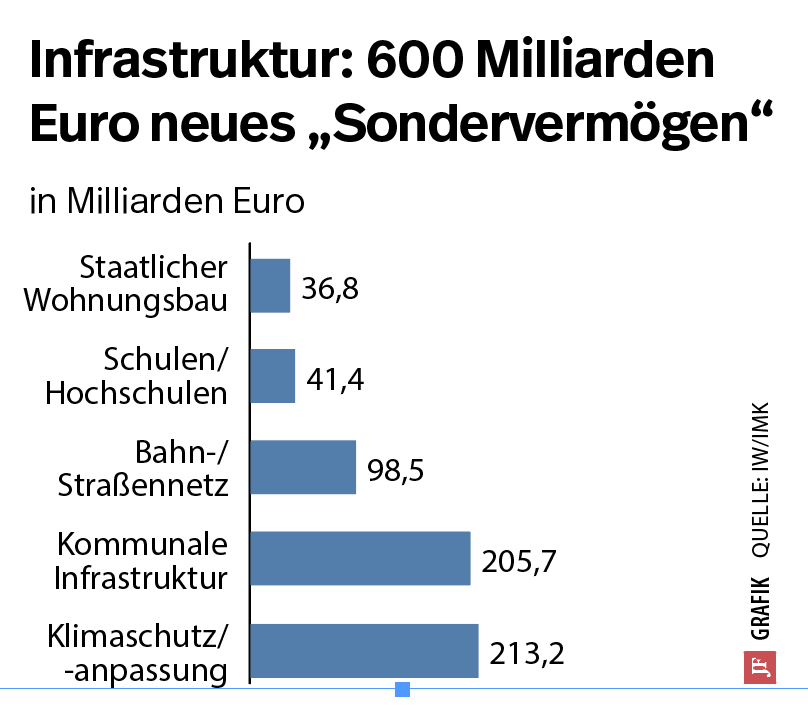

If the DGB and the employer agree, then there must be something special going on. In a joint short study The scientific institutes of both collective bargaining parties have highlighted the shortcomings of infrastructure policy. The employer-related Institute for the German Economy (IW) and the union’s own Institute for Macroeconomics and Economic Research (IMK) see an investment gap of almost 600 billion euros in public investments.

That is 14 percent of annual economic production or more than a quarter of the total state budget. The backlog must be closed within ten years through massive investments in roads, rail networks, schools and climate protection. Economists from Cologne and Düsseldorf presented a similar calculation five years ago. At the time, the deficit in public investment was estimated at 460 billion euros. In the meantime, however, climate protection targets have been further tightened and construction prices have risen enormously.

The gigantic task can no longer be financed from the current budgets. To achieve this, special loans would have to be taken out: by weakening the debt brake or by creatively circumventing national and EU-wide budget rules. These are remarkable recommendations. In fact, independent scientists should look critically at politicians and not propose dubious funding schemes to cover up their failures. Ironically, the study is also titled “Reloaded for Sound Financial Policy,” a framework that could come from Habeck.

Reducing the debt burden is not a reason for the investment deficit

Regarding the core question, the authors, including the two institute heads Michael Hüther (IW) and Sebastian Dullien (IMK), are absolutely right. For example, the condition of Germany’s roads is tragic, the punctuality and service of the railways are often reminiscent of that of a developing country, and there are also many problems at schools and universities. Unfortunately, the reasons for this are not discussed at all. Instead, the authors debunked the politicians’ excuse that the state does not have enough money.

State revenues are at a record high, as is the state’s share of economic output, which recently reached 51 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). Scientists are not docile servants of the government, but must speak out unpleasant truths openly. In any case, the institutions are making it too easy for themselves by merely recommending taking on more debt, in violation of the budget rules, to which politicians have of course responded enthusiastically.

In reality, the problem goes back to decades of failures and unwanted developments. And the investment gap cannot in any way be explained by the debt brake, which has only been in the Basic Law since 2009. Rather, it is a specifically ‘German disease’, like the one in Economic service (22/7) published study by Felix Rösel and Julia Wolffson (TU Braunschweig) argues. With a public investment rate of 2.1 percent of GDP, Germany is well below the European average, which at 3.7 percent has been almost twice as high over the past twenty years.

Bureaucracy as the root of all evil

This cannot be attributed to overly strict budgetary rules, as shown by the analysis of the Braunschweig economists. On the contrary, completely different factors that have little to do with a lack of money are decisive for the German problem. First of all, these are the long and cumbersome approval procedures, a lack of planning capacity on the part of the authorities and, last but not least, the enormous political and legal resistance to anything that could in any way disrupt the peace of residents. Other government advisors had complained about this before, such as the Scientific Advisory Council of the Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs in 2020. Billions of dollars in infrastructure funding often go unused because states and municipalities lack projects ready for implementation despite the enormous need.

The Board of Experts points out in its current spring report that things can also be done differently. By law, approval requirements and environmental impact assessments may be omitted for the renovation of bridges. People don’t care about green pet projects like wind turbines and solar fields anyway. It is therefore difficult to understand why, for example, important municipal road projects such as bypasses or the construction of roundabouts have been postponed for decades, sometimes arbitrarily.

Denmark shows: there is another way

Countries such as Denmark have long ensured that building laws can be quickly enforced here. And that doesn’t cost any money; on the contrary, it saves billions. However, such possibilities are not mentioned at all in the joint IW/IMK study. What also remains undiscussed is where the construction capacity should actually come from in order to quickly build all missing investment projects from the ground.

The uncritical acceptance of the so-called climate goals is also strange. These not only limit overall CO₂ emissions, but also include a veritable mass of individual specifications and projects that cause unnecessarily high costs. For example, the costs of insulation measures in buildings often bear no reasonable relationship to the greenhouse gases saved as a result. Nevertheless, according to the recommendation of the IW/IMK study, an additional EUR 200 billion would have to be spent on these types of climate protection investments alone. From 2027, emissions in the construction sector will be capped across the EU through emissions trading II. But the study also makes no mention of this. With a bachelor’s thesis you would say: insufficient, please rework it.

Prof. Dr. Ulrich van Suntum taught economics at the Westphalian Wilhelms University in Münster until 2020.