Viewed benignly, the encyclopedic art museum is a great public library of things, illuminating the brilliant variety and shared impulses of our species, and promoting intercultural understanding and admiration. Viewed less benignly, it has been cast as the well-spoken child of imperialist shopaholics and kleptomaniacs who appropriated the art of other people to tell flattering tales about themselves.

Museums have long contested this characterization on grounds both pragmatic (their ability to protect and care for the world’s treasures) and high-minded—the belief that convening things from everywhere enables them to tell a sweeping, global story about what it is to be human. The 2002 “Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums,” signed by the directors of 18 world-famous institutions, put the claim succinctly: “Museums serve not just the citizens of one nation but the people of every nation.” It’s a fine sentiment, but the fact that every one of those 18 museums is in Europe or North America raises obvious questions about just how those peoples of other nations are being served. This geographic lopsidedness has led critics to challenge not only the museums’ rights to the objects in their care, but also the histories those objects have been arranged to illustrate.

If “every traveller is necessarily the hero of his own story,” as the Scottish novelist John Galt observed in 1812, then so is every culture. The encyclopedic museum as we know it, like the academic disciplines of art history and archaeology that underpin it, first flourished in the 19th century. Intentionally or not, it has tended to convey a particular worldview, described by the Senegalese philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne as a “unilinear path, leading from Athens to Rome, and from Rome to London, Paris, or Heidelberg … Everything else outside of it is a curiosity.” There is a center and a periphery. All roads and grand marble staircases lead to us.

“Africa & Byzantium,” the unexpected and revelatory exhibition now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (it travels to the Cleveland Museum of Art in April), presents an alternative to that unilinear path—something more like a transit map, where different lines run in parallel, loop, diverge, and offer various points of transfer. Organized by Andrea Myers Achi, the Met’s associate curator of Byzantine art, the show and its catalog share an ambitious goal: “to present a narrative of Africa unconnected to colonialism and its legacies.”

Having thus dismissed the dominant framework that Western institutions have used to understand Africa (a framework that serves to keep the West at the center of the conversation, as perps if no longer heroes), this densely packed show surveys roughly 1,500 years and millions of square miles, telling viewers something about empire, something about religion, and a good deal about the human compulsion to make beautiful things. It offers no simple takeaway—no coherent tale of splendor and decline (or vice versa), no commanding center and fawning periphery. Instead it demonstrates how an encyclopedic museum can be part of the solution, rather than just a metonym for the problem.

Cleopatra and Mark Antony notwithstanding, one might forget that the Roman empire’s encirclement of the Mediterranean included its African shores. That those African provinces remained more or less united under Byzantine governance for three centuries, from Emperor Constantine the Great’s reign (306–37 C.E.) onward, may come as complete news. The 1,000-year history of Byzantium—the predominantly Greek-speaking continuation of the Roman empire, whose capital Constantine relocated to what is now Istanbul—has been the subject of previous game-changing exhibitions at the Met, but the current show is not really concerned with goings-on in Constantinople. Its purview is the swath of Africa that once lay within Byzantium’s sphere of influence—largely Christian territories that stretched from Ethiopia (which was never part of the empire) to Morocco (which was).

The opportunity presented by “Africa & Byzantium” is not just to see how African artists made things that are easy to admire using our usual standards, though those abilities are demonstrated fulsomely. It is also to stretch those standards in new directions. After all, for generations, Byzantium itself was seen as an error, extraneous to the triumphant saga of European civilization from Greco-Roman antiquity through the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, and eventual global domination. The 18th-century English historian Edward Gibbon thought Byzantium “a tedious and uniform tale of weakness and misery.” In the following century, the historian W. E. H. Lecky went further, calling it “the most thoroughly base and despicable form that civilisation has yet assumed.” Its gilded icons, with their sad eyes and balletic limbs, may have been necessary stepping stones to Giotto and Botticelli and all the rest, but to many they appeared crude, repetitious, and more than a little blingy. Those earlier exhibitions at the Met played no small part in turning this perception around, and “Africa & Byzantium” extends the effort both chronologically and geographically.

The African provinces were important to Rome and Byzantium not just as pieces of some proto–Great Game strategy, but because they were rich. The breadbasket of the empire, North Africa and Egypt were home to vibrant, cosmopolitan societies and diverse economies. For Romans of Constantine’s era, Britain was a hardship post; Africa was a plum. A century after Constantine, Saint Augustine, a Berber from what is now Algeria, asked: “Who now knows which peoples in the Roman Empire were what, since we have all become Romans?” Two centuries after that, Emperor Heraclius considered moving the capital from Constantinople to Carthage, in present-day Tunisia. Visitors to the exhibition would do well to leave at the door any contemporary assumptions about the geography of wealth, power, religious animosity, and ethnic identification.

The curators have scored an impressive array of loans, and the exhibition opens with a spectacular mosaic sent by the Louvre. In tesserae that once graced the floor of a villa near Carthage, life-size, remarkably individuated servants wander about portaging food and drink, each casting his own abbreviated shadow on the floor he is built into. Display cases nearby abound with further evidence of the good life: gold jewelry chockablock with pearls and gems; intricate textiles adorned with mounted warriors, dancing maenads, and a vision of Artemis hovering in midair. A woman is shown on a painted shroud dressed in a simple shift and fetching red socks of translucent silk, probably imported from India.

Another large mosaic, known as the “Lady of Carthage,” portrays a female figure holding a scepter and raising her right hand in benediction. A nimbus illuminates her updo, but over her shoulders she wears a man’s cloak, fastened with an imperial pin. This mash-up of allusions—imperial authority, Christian divinity, male and female—has never been decisively resolved: It has been read as a portrait of Empress Theodora, a personification of the city of Carthage, an allegory of imperial power, and perhaps an archangel.

For all its visual dazzle, this is a measured and scholarly show, and the three dozen experts who contributed to the exhibition catalog are forthright about how little is known. Given the geographic expanse of Byzantine trade, even basic information about where and when an object was produced can be uncertain. Found in one place, it might have been made thousands of miles away, and slapdash archaeology in the 19th and early 20th centuries makes it hard to date things with any accuracy.

All of this complicates interpretation. The exhibition includes mosaics from a site in the Tunisian town of Hammam-Lif. Discovered by French soldiers in 1883, the building’s elaborate floor mosaics were hacked into sections and sold off. The ones in the exhibition, on loan from the Brooklyn Museum, include a lithe date palm and an affable lion amid flowers that could have adorned many different kinds of buildings, but also two menorahs. These identified the building as a synagogue and not, as originally assumed, a church, though scholars question the presumption of “strict aesthetic differences between so-called Jewish, Christian and Pagan symbols.” Nor is it clear how worshippers would have used this floor. As the art historian Liz James points out in the catalog, many floor mosaics included sacred imagery and patron portraits. “Were these also walked over, brushed and scrubbed clean, or overlaid with tables and chairs? Did they offer the enslaved a chance to grind their heels into the slaveholders’ face”? It would be nice to know.

What is clear is that over the centuries, imitation and invention ebbed and flowed across these expansive territories as Egyptians and Greeks, Latin-speaking Jews and Berber-speaking Christians came and went. The elites, at least, were multilingual, and religious artifacts could be surprisingly interdenominational. A Nubian pot from the first centuries of the Common Era is decorated with a stamp that seems to split the difference between an Egyptian ankh and a Christian cross; an oil lamp bears the image of a menorah as well as Christ stomping on the head of a serpent. The face of the “Lady of Carthage,” whoever she is meant to be, has the same oversize eyes, strong brows, long nose, and pursed lips as the goddess Isis in a second-century Egyptian panel painting. Having made her way from the Egyptian pantheon to Greco-Roman cult status, Isis—often shown with her infant son, Horus, in her lap—then provided a smooth segue to the imagery of the Virgin Mary.

Christianity came early to Africa. Mark the Evangelist established the See of Alexandria in the mid-first century, and Christian monasticism originally flourished in the Egyptian desert. The remains of the Egyptian martyr Saint Menas were the focus of a thriving pilgrimage route centuries before Santiago de Compostela, and flasks stamped with his image, meant for holding oil or water that had touched the relics, have been unearthed as far afield as Cheshire, in the north of England. Four appear in the exhibit.

The Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine, in Sinai, was another popular site of pilgrimage (despite her frequent blondness in European painting, Catherine was also Egyptian), and its remoteness was crucial to the preservation of early Christian art during the iconoclasms that swept through Byzantium in the eighth and ninth centuries. Most of the icons that survived were (and still are) in its collection. Several have been loaned to this exhibition, including a famous sixth-century painting of the Virgin and Child, perhaps the oldest such image in existence. Flanked by standing soldier-saints, a somber Mary holds her baby in her lap. Behind her, a pair of angels lean left and right to make room for the small hand of God reaching down from the top edge, as if to adjust a bit of drapery. The arrangement is regimental in its symmetry, yet the faces are subtle and expressive, and the infant far more natural in attitude than the wizened homunculi that crop up in so many European pictures. In turning her large eyes upward and to the left, looking beyond us to something we cannot see, Mary, too, echoes that second-century Isis.

By the time of the iconoclasms, Africa had slipped from Byzantine control. The Alexandrian Church broke away in 451, and the arrival of Islamic armies in the seventh century eventually expelled the empire from the continent. Roughly a third of “Africa & Byzantium” postdates African Byzantium itself. Religion replaces imperial oversight as the connecting thread: Manuscripts and icons from monasteries within Islamic Egypt attest to enduring Christian communities. There’s a wonderful Saint George with a head of pom-pom-like curls, painted centuries after the Islamic conquest. But the exhibition turns south to the Christian kingdoms of Nubia (now southern Egypt and northern Sudan) and Aksum (contemporary Ethiopia and Eritrea), never ruled by Byzantium but part of Byzantine Africa’s cultural and religious milieu.

Both were early adopters of Christianity, and both were wealthy and well connected, controlling trade routes that stretched from the Sahara to the Indian Ocean. Nubia, which once supplied pharaohs to Egypt, later oriented itself to Hellenistic Greece and then to Byzantium. For more than 1,000 years, Greek was its lingua franca, and its kings were known by the Greek word basiliskos. The exhibition includes pottery painted with delicate vines in a Greek manner, silver crowns with allusions to Horus and Isis, and an astonishing bridal chest, in the form of a multistory building, its 21 pedimented windows fitted with ivory panels. Its mythological decoration mixes Aphrodite-like naked women, tumbling men, and satyrs (penises prominently featured). Abjuring gold and glittering glass mosaics, these beautifully constructed artifacts are less flashy than much of what precedes them in the show.

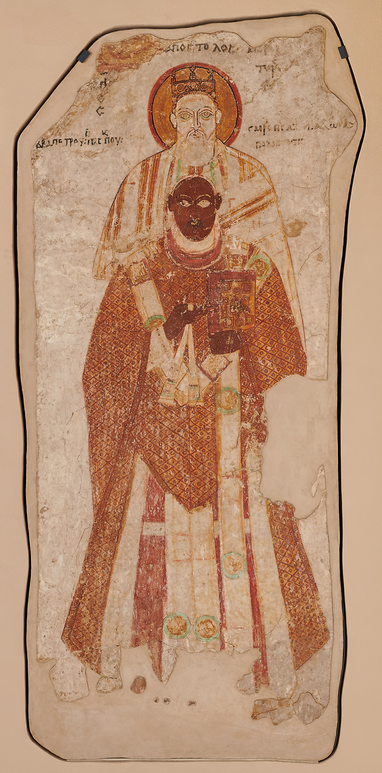

The most commanding presence in “Africa & Byzantium” is a tenth-century Nubian bishop, Petros, portrayed in a wall painting with his namesake, Saint Peter. Resplendent in his liturgical robes, Petros stands in front of the saint, who places paternal hands on his shoulders. Facing forward, larger than life, Petros and Peter look out at us with serene and sober assurance. The bishop’s densely patterned robe, brown hands, and dark head stand out sharply against Peter’s pale cloak, white skin, and beard, which are set against the saint’s dark nimbus and crown.

What this attention to skin color signifies is an open question. Might it be an attempt at realism—distinguishing a saint native to the Levant from a local clergyman? Or perhaps a way to distinguish the spiritual realm from the material one? (Saint Peter is so wan, he’s almost see-through.) Contemporary instincts—to construe attention to skin color, for example, as an assertion of racial or ethnic hierarchies—offer little guidance for images made centuries before colonialism’s heyday. Egyptian textiles used black silhouettes for figures that might be intended to be Nubians or “black Indians,” as well as for the flying Artemis. The servants in the spectacular mosaic from the Louvre might be the cast for a Benetton ad: light-skinned, dark-skinned, curly-haired, straight-haired, all impressively buff—though all most likely enslaved.

The last of the Nubian kingdoms collapsed in 1504, having outlived Byzantium by half a century (Constantinople fell to the Ottomans in 1453). Ethiopia, the second-oldest Christian state in the world (after Armenia), remained the last Christian empire in Africa. It took this status to heart: “As the sun is greater than the moon … so the faith of Ethiopians is greater than that of other Christians,” the 15th-century emperor Zara Yaqob is said to have proclaimed. Though distinct in many practices, the Ethiopian Church received its patriarchs from Alexandria and shared its appreciation of devotional images. But while Egyptian Christians now resided within Islamic caliphates, medieval Ethiopia thrived as a dynamic entrepôt.

Trade and travel would have brought Ethiopian artists face-to-face with Byzantine-style icons, Western European painting, Islamic decorative objects, and Indian textiles. A Venetian painter, Nicolò Brancaleon, worked in the Ethiopian court around 1500. When the Jesuits arrived in 1557, hoping to convert the empire to Roman Catholicism, they brought European engravings, and though their conversion effort eventually failed, the engravings left their mark, especially one depicting a Virgin and Child icon in the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, in Rome.

The central panel of a large 17th-century Ethiopian triptych mimics the distinctive pose of the Roman icon—the child is leaning back in Mary’s crossed arms to gaze at her as he makes a gesture of blessing—but everything else is different. In place of the engraving’s black and white, there is bold color. In place of the studious proportions and stony mien, we get oversize heads with theatrical eyes, sidelong glances, and dynamic gestures. Pattern enlivens clothing, backdrops, even nimbuses. Stasis gives way to vibrant action.

The degree to which Ethiopians were open to new ideas while remaining utterly self-assured in their own aesthetic is manifest in a pocket-size diptych that ties together (literally, with cord) an Ethiopian Saint George and a Virgin and Child, probably painted in Crete. With her gold backdrop, elongated fingers, and complex drapery, the Virgin follows a typically Byzantine model. The mounted Saint George, in contrast, comes to life in animated outline, his cloak airborne behind him, taut as a bat wing, rather than falling in soft pleats. Bypassing the naturalism that tethered Byzantine art to Hellenistic Greece at one end and the Renaissance at the other, Ethiopian images invite the viewer’s eye to dance across a surface, leaping from point to point.

This is not what European painting has taught us to expect from reverential art, and it raises the vexed question of what constitutes greatness in a world not our own. About 600 years ago, Western Europeans developed a taste for illusionistic depictions of figures in space. Even now, Liz James notes in the catalog, this preference influences the evaluation of antique mosaics, awarding favored status to those that look most like paintings created centuries later. “We might do better,” she proposes, “thinking about ‘good’ and ‘poor’ mosaics in terms of the technical skill involved.”

Much of art history, however, is predicated on the idea that style can be a proxy for a worldview. Knowing something about the one may change how we see the other. In the case of Ethiopia, a continuous, well-documented religious tradition is here to help. In his catalog essay, Jacopo Gnisci, a lecturer at University College London, reproduces two 14th-century crucifixion scenes: a gilded Byzantine icon of the contorted Christ, dead on the cross between two grieving mourners, and an Ethiopian parchment painting in which the two thieves crucified with Jesus turn startled eyes on an empty central cross, while the Lamb of God floats above. These divergent portrayals illuminate the pivotal theological dispute about the nature of Christ that had separated the African Church from its parent in 451. The Byzantine artist, believing Christ to be both human and divine, emphasizes corporeal suffering. The Ethiopian artist, viewing Christ as entirely divine, pictures only the transcendent spirit. Where the first aims “to evoke a sense of mourning,” Gnisci writes, the other frames “the episode in triumphal terms.” Sprightliness of style, it turns out, can be another form of reverence.

“Africa & Byzantium” contains much that will capture attention and immediately impress, and it’s also full of things that won’t—tiny coins and shards of pottery inscribed in languages few visitors will be able to decipher. But this is inherent in the mission of the encyclopedic museum as well—a reminder that not everything can be yours at a glance. Finding the magic may require real work.

And yet, how can you not warm to the ratty, place-mat-size papyrus bearing a Coptic spell (the label explains) for acquiring a beautiful voice, with its swift sketch of someone waving their arms with the frantic energy of a Roz Chast character? Bishop Petros’s image may inspire awe, the Virgin and Child from Saint Catherine’s may stop us in our tracks with the intensity of its devotion, but the papyrus reaches out like a hand across time. We may no longer write spells on papyrus, but a Google search returns more than 30,000 hits for videos on how to acquire a beautiful voice.

Empire makes for compelling narratives, in art as in movies, and museums have long structured themselves in various heliotropic halls—Egypt, Greece, Paris, New York—each with its own shining cultural sun toward which the outer bits turn, recipients of light rather than instigators. But we all know that cultural production is less like a solar system or an org chart than a boisterous Venn diagram.

Passing through the Met’s Greek and Roman galleries after “Africa & Byzantium,” I found that artworks that had gone unnoticed on the way in now popped out with a fresh “I think you’ve met my cousin” semi-familiarity. Upstairs, the museum has reopened its European-paintings galleries with an entirely new hanging. Echoing Souleymane Bachir Diagne, the text that greets visitors acknowledges, “Art has often been enlisted to promote a unified idea of Europe, a ‘Western tradition’ contrasted with the rest of the globe,” and promises to draw out “the inconsistencies and tattered edges of long-dominant storylines.” The Raphaels and Rembrandts are still there, but so are 18th-century paintings made in South America and 21st-century ones made in North America. And at the center of the medieval hall that functions as the nave of this cathedral of art stands a display of elaborate Ethiopian metalwork crosses. Behind them, in December, stood the Met’s enormous Christmas tree.

This article appears in the March 2024 print edition.