When big pharmaceutical companies are confronted over their exorbitant pricing of prescription drugs in the US, they often retreat to two well-worn arguments: One, that the high drug prices cover costs of researching and developing new drugs, a risky and expensive endeavor, and two, that middle managers—pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), to be specific—are actually the ones price gouging Americans.

Both of these arguments faced substantial blows in a hearing Thursday held by the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, chaired by Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.). In fact, pharmaceutical companies are spending billions of dollars more on lavish executive compensation, dividends, and stock buyouts than they spend on research and development (R&D) for new drugs, Sanders pointed out. “In other words, these companies are spending more to enrich their own stockholders and CEOs than they are in finding new cures and new treatments,” he said.

And, while PBMs certainly contribute to America’s uniquely astronomical drug pricing, their profiteering accounts for a small fraction of the massive drug market, Sanders and an expert panelist noted. PBMs work as shadowy middle managers between drugmakers, insurers, and pharmacies, setting drug formularies and consumer prices, and negotiating rebates and discounts behind the scenes. Though PBMs practices contribute to overall costs, they pale compared to pharmaceutical profits.

Rather, the heart of the problem, according to a Senate report released earlier this week, is pharmaceutical greed, patent gaming that allows drug makers to stretch out monopolies, and powerful lobbying.

On Thursday, the Senate committee gathered the CEOs of three behemoth pharmaceutical companies to question them on the drug pricing practices: Robert Davis of Merck, Joaquin Duato of Johnson & Johnson, and Chris Boerner of Bristol Myers Squibb.

“We are aware of the many important lifesaving drugs that your companies have produced, and that’s extraordinarily important,” Sanders said before questioning the CEOs. “But, I think, as all of you know, those drugs mean nothing to anybody who cannot afford it.”

America’s uniquely high prices

Sanders called drug pricing in the US “outrageous,” noting that Americans spend by far the most for prescription drugs in the world. A report this month by the US Department of Health and Human Services found that in 2022, US prices across all brand-name and generic drugs were nearly three times as high as prices in 33 other wealthy countries. That means that for every dollar paid in other countries for prescription drugs, Americans paid $2.78. And that gap is widening over time.

Focusing on drugs from the three companies represented at the hearing (J&J, Merck, and Bristol Myers Squibb), the Senate report looked at how initial prices for new drugs entering the US market have skyrocketed over the past two decades. The analysis found that from 2004 to 2008, the median launch price of innovative prescription drugs sold by J&J, Merck, and Bristol Myers Squibb was over $14,000. But, over the past five years, the median launch price was over $238,000. Those numbers account for inflation.

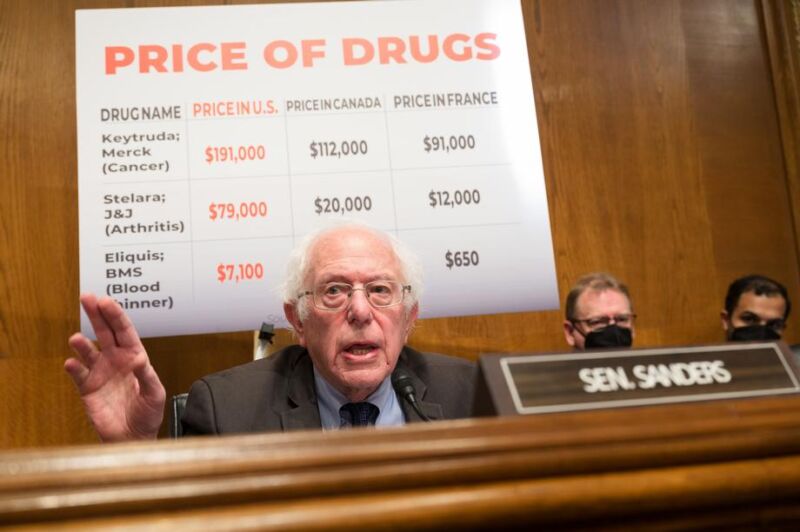

The report focused on high-profit drugs from each of the drug makers. Merck’s Keytruda, a cancer drug, costs $191,000 a year in the US, but is just $91,000 in France and $44,000 in Japan. J&J’s HIV drug, Symtuza, is $56,000 in the US, but only $14,000 in Canada. And Bristol Myers Squibb’s Eliquis, used to prevent strokes, costs $7,100 in the US, but $760 in the UK and $900 in Canada.

Sanders asked Bristol Myers Squibb’s CEO Boerner if the company would “reduce the list price of Eliquis in the United States to the price that you charge in Canada, where you make a profit?” Boerner replied that “we can’t make that commitment primarily because the prices in these two countries have very different systems.”

The powerful pharmaceutical trade group PhRMA, published a blog post before the hearing saying that comparing US drug prices to prices in other countries “hurts patients.” The group argued that Americans have broader, faster access to drugs than people in other countries.

Enrichment over R&D

Sanders, meanwhile, highlighted the effects of this pricing. Thirty-one percent of Americans have reported not taking their medications as prescribed due to costs. Hundreds of people have set up GoFundMe pages to pay for Merck’s cancer drug, Keytruda, including a woman in Nebraska named Rebecca. The mother of two who worked at a school cafeteria died of cancer after raising only $4,000 for her Keytruda infusions that cost $25,000 every three weeks, Sanders said.

While the CEOs defended their pricing at the hearing, Sanders and his committee’s report noted that pharmaceutical companies are spending far more on executives and stockholders than R&D. In 2022, J&J made $17.9 billion in profits, and its CEO received $27.6 million in compensation. That year, the company spent $17.8 billion on stock buybacks, dividends, and executive compensation, while the company spent just $14.6 billion on R&D, the report states. “In other words, the company spent $3.2 billion more enriching executives and stockholders than finding new cures,” it concludes.

In 2022, Bristol Myers Squibb also spent $3.2 billion more on stock buybacks, dividends, and executive compensation than R&D—$12.7 billion on executives and stockholders compared with $9.5 billion on R&D. That year, the company made $6.3 billion in profits, and its former CEO made $41.4 million in compensation.

Some Republicans on the committee pushed back on Democratic criticism of pricing, arguing that pricing is what the market will bear. “In capitalism, if you’re running an enterprise where you have a fiduciary responsibility to your owners, you try and get as high a price as you can,” Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) said. “That’s what you try and do. You try and make as much profit as you can. That’s how free enterprise works. You think Chevrolet sits back and says, ‘Gosh, how can we get the price of this Chevrolet down?’ No, it’s like, ‘How high a price can I get and maximize the profit for my shareholder?'” He went on to describe price controls as “socialism lite.”

“The root of the problem”

Peter Maybarduk, the director of the Access to Medicines program at Public Citizen, a watchdog organization, who also testified at the hearing, hit back at the main pharmaceutical talking points along with Sanders. That included noting that the makers of the 10 drugs selected for the first round of Medicare price negotiation spent $10 billion more on self-enriching activities than R&D.

Like Sanders, Maybarduk dismissed the idea that pharmaceutical middle managers were the main problem in US drug pricing.

“We heard some wild stuff up here this morning, including a lot of blaming middlemen for the problem of high prices,” Maybarduk said in a response to a question from Sanders. “Drugmakers’ high prices are the whole reason that we have a middlemen problem. It’s because we have exceedingly high prices at the outset that there’s an attractive market for middlemen to enter. But the fish rots from the head. If you break up the market, if you look at where the revenue is, drug makers capture two-thirds, $323 billion, pharmacy benefit managers are a small slice, $23 billion. You can’t fix the problem of the pharmaceutical industry by going off middlemen who are just trying to skim off the top. You have to get to the root of the problem which is the monopoly power.”

The Senate report pointed to patent gaming that allows pharmaceutical companies to hold on to monopolies for extended periods. It highlighted that Johnson & Johnson, Merck, and Bristol Myers Squibb have accumulated dozens of patents on individual drugs, creating “patent thickets.” With the dense protection, pharmaceutical companies can delay low-cost alternatives from entering the market. And, if that isn’t enough, pharmaceutical companies also spend hundreds of millions of dollars on political contributions and lobbying to protect their interests.