File this one under “Studies We Wish Had Let Us Remain Ignorant.” Scientists at the University of Arizona decided to investigate whether closing the toilet lid before flushing reduces cross-contamination of bathroom surfaces by airborne bacterial and viral particles via “toilet plumes.” The bad news is that putting a lid on it doesn’t result in any substantial reduction in contamination, according to their recent paper published in the American Journal of Infection Control. The good news: Adding a disinfectant to the toilet bowl before flushing and using disinfectant dispensers in the tank significantly reduce cross-contamination.

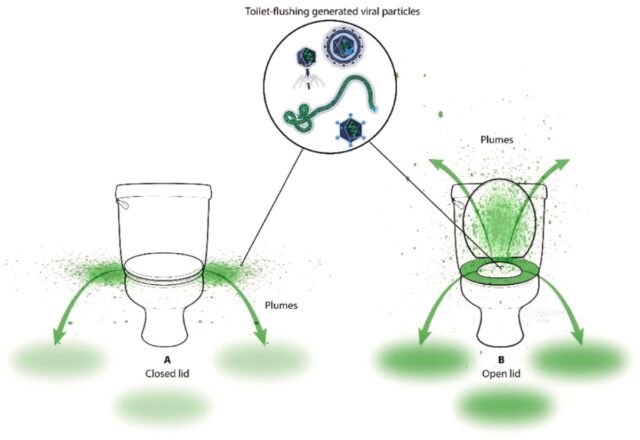

Regarding toilet plumes, we’re not just talking about large water droplets that splatter when a toilet is flushed. Even smaller droplets can form and be spread into the surrounding air, potentially carrying bacteria like E. coli or a virus (e.g., norovirus) if an infected person has previously used said toilet. Pathogens can linger in the bowl even after repeated flushes, just waiting for their chance to launch into the air and spread disease. That’s because larger droplets, in particular, can settle on surfaces before they dry, while smaller ones travel further on natural air currents.

The first experiments examining whether toilet plumes contained contaminated particles were done in the 1950s, and the notion that disease could be spread this way was popularized in a 1975 study. In 2022, physicists and engineers at the University of Colorado, Boulder, managed to visualize toilet plumes of tiny airborne particles ejected from toilets during a flush using a combination of green lasers and cameras. It made for some pretty vivid video footage:

“If it’s something you can’t see, it’s easy to represent it doesn’t exist,” study co-author John Grimaldi said at the time. They found that the ejected airborne particles could travel up to 6.6 feet per second, reaching heights of 4.9 feet above the toilet within 8 seconds. And if those particles were smaller (less than 5 microns), they could hang around in that air for over a minute.

More relevant to this latest paper, it’s been suggested that closing the lid before flushing could substantially reduce the airborne spread of contaminants. For example, in 2019, researchers at University College Cork deployed bioaerosol sensors in a shared lavatory for a week to monitor the number and size of contaminant particles. They concluded that flushing with the toilet lid down reduced airborne droplets between 30 and 60 percent. But this scenario also increased the diameter of the droplets and bacteria concentration. Leaving the lid down also means the airborne microdroplets are still detectable 16 minutes after flushing, 11 minutes longer than if one flushed with the lid up.

“Unfortunately, the possible benefit toilet lid closure during flushing for reducing viral contamination has not been demonstrated empirically,” the authors of this latest study wrote in their paper. “In addition, other activities in the restroom, such as cleaning the toilet bowl, may result in the generation of aerosols.” So Stephanie Boone and co-authors decided to rectify this gap in the literature.

The scientists conducted their experiment with E. coli (as a host bacteria) and coliphage MS2; the latter is not a human or animal pathogen but serves as a useful model. The public toilet used in the experiment was located in a stall in the restroom of an office building. That toilet was tankless, relying on water line pressure for flushing, with no lid and a U-shaped seat with a gap in the front. The home toilet was a standard siphonic toilet with a tank and lid in a private residence; there was no gap on the center of the seat.

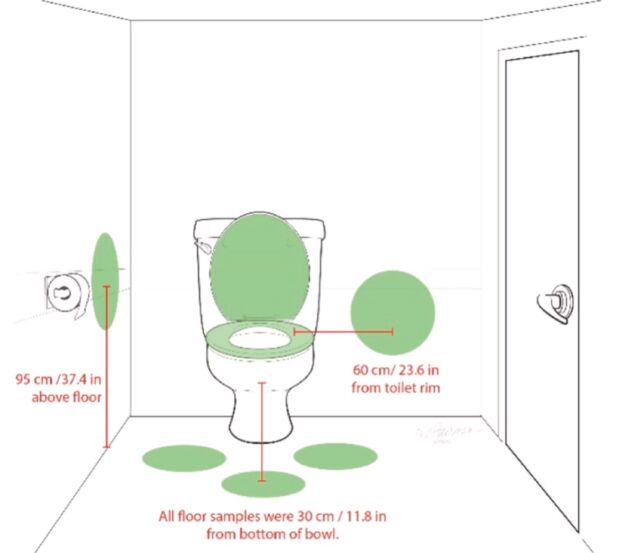

Toilet bowls were seeded with MS2 and flushed. After one minute, samples were taken from various restroom surfaces: the top and bottom of toilet seats, the bowl rim, three locations on the floor, and the right and left walls. The team also conducted a similar experiment involving cleaning the bowls with toilet brushes, both with and without Lysol toilet bowl cleaner. All those samples were then tested for MS2 contamination.

The results: both the tops and bottoms of the lidless public toilet seats had more contamination compared to household seats, but otherwise, there was no statistical significance in the degree of contamination between lidless public toilets and household toilets with lids. And the surface contamination did indeed persist even after repeated flushes. The toilet seat was the worst offender with the greatest degree of contamination, which the authors suggest “reflects the airflow that occurs during toilet flushing, i.e., largely around the top and bottom of the toilet seat.” That same airflow is likely a factor in spreading the contamination to restroom floors and walls.

Perhaps the least surprising finding is that rigorous cleaning with a toilet bowl brush and Lysol reduced the contamination by 99.99 percent compared to cleaning with just a brush. Therefore, “The most effective strategy for reducing restroom cross-contamination associated with toilet flushing include the addition of a disinfectant to the toilet bowl before flushing and the use of disinfectant/detergent dispensers in the toilet tank,” the authors concluded. They also recommend regularly disinfecting all restroom surfaces after flushing or cleaning with a toilet brush in health care facilities—which often have a lot of immunocompromised people—and if someone in your house has an active infection like norovirus.

Got it. Pardon us while we scrub our toilet bowls with Lysol and stock up on toilet tank disinfectant dispensers.

American Journal of Infection Control, 2024. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajic.2023.11.020 (About DOIs).