In December 2013, a curator and archaeologist purchased an antique silk dress with an unusual feature: a hidden pocket that held two sheets of paper with mysterious coded text written on them. People have been trying to crack the code ever since, and someone finally succeeded: University of Manitoba data analyst Wayne Chan. He discovered that the text is actually coded telegraph messages describing the weather used by the US Army and (later) the weather bureau. Chan outlined all the details of his decryption in a paper published in the journal Cryptologia.

“When I first thought I cracked it, I did feel really excited,” Chan told the New York Times. “It is probably one of the most complex telegraphic codes that I’ve ever seen.”

Sara Rivers-Cofield purchased the bronze-colored silk bustle dress with striped rust velvet accents for $100 at an antique shop in Maine, noting on her blog that it was in a style that was fashionable in the mid-1880s among middle-class or well-off women. There wasn’t any fitted boning in the bodice, so the dress was meant to be worn with a corset. It had a draped skirt and bustle with metal buttons decorated with an “Ophelia motif.” While the dress had been machine-stitched, the original buttons had been sewn by hand. A tag with the name “Bennett” was sewn into the bodice.

Rivers-Cofield also noted the ingenious structure of the bustle, which used built-in channels for flexible wires to achieve just the right amount of puff, combined with strategic tacking to keep “the bustle bunched in all the right places.” One bustle pin was still in place, and Rivers-Cofield thought it was used to pull up a layer of the overskirt to expose a bit of the hem ruffle “for a little peek-a-boo with onlookers.” Such pins often show up during excavations of 19th century sites, so she was delighted to find one in situ. “There is one Baltimore laundry site in particular where drainage pipes were found absolutely clogged with pins, buttons, and other clothing attachments—as if launderers put the clothes through a rough washing process … even if removable pins were still on them,” she wrote.

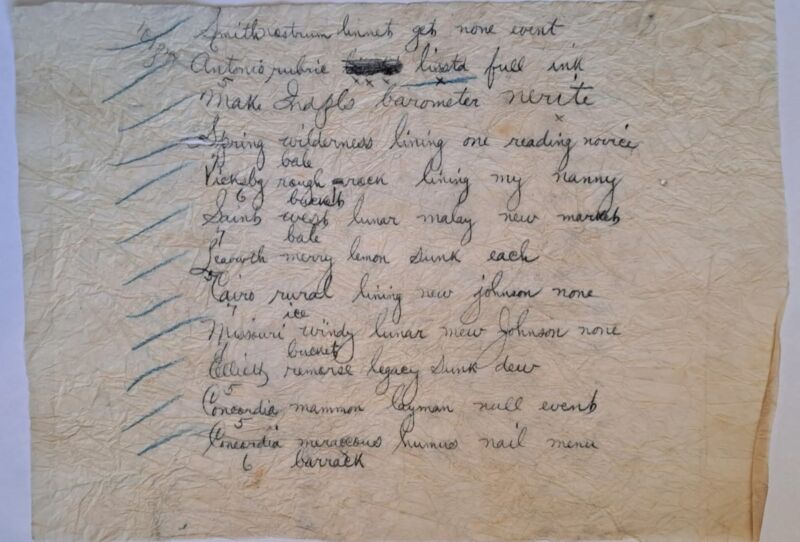

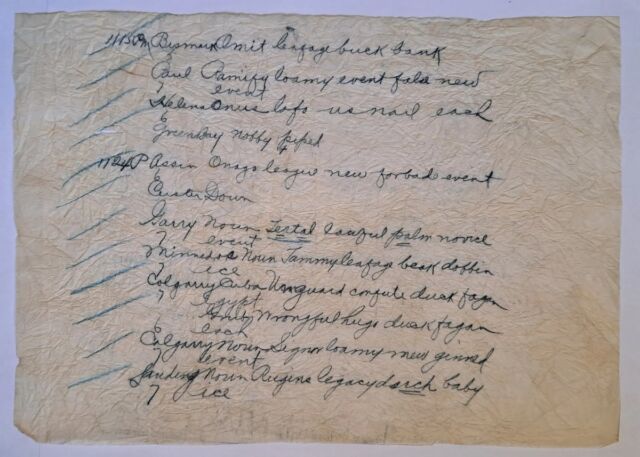

But an even more intriguing discovery awaited. When Rivers-Cofield turned the dress inside-out, she found a small hidden pocket. Many women’s dresses of the era had pockets, but this one would only be accessible by hiking up the overskirt. She puzzled over why anyone would make a pocket so inaccessible and thought it might have been used to smuggle messages. Hidden inside, she found two sheets of wadded-up translucent paper measuring about 7.5 inches by 11 inches. The text on each sheet consisted of 12 lines of recognizable common English words—except they made no sense. “Bismark omit leafage buck bank”? “Paul Ramify loamy event false new event”?

No wonder Rivers-Cofield’s blogged reaction was a simple “What the—?” She thought it might be some kind of list or a writing exercise and posted all the details on her blog, hoping that “there’s some decoding prodigy out there looking for a project.” It became known as the “Silk Dress cryptogram.” German cryptoblogger Klaus Schmeh noted in 2017 that he considered it to be among the top 50 such coded messages yet unsolved.

Schmeh first wrote about the Silk Dress cryptogram in 2014 and invited readers to weigh in. By 2017, he had concluded that the text was probably a telegram—possibly several telegrams—and that the words were chosen from an 1880s code book. There was a numeral at the start of most lines that seemed to indicate the number of words, and each sheet had what appeared to be the time of day written at the top.

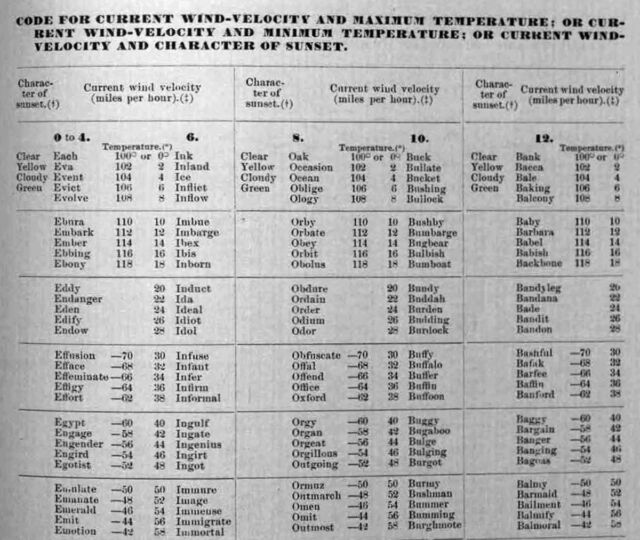

Chan started working on the code in the summer of 2018 but didn’t initially make much progress and abandoned the project a few months later. He picked up the challenge again toward the end of 2022 and thought it might be a telegraphic code. With the invention of the telegraph, “For the first time in history, observations from distant locations could be rapidly disseminated, collated, and analyzed to provide a synopsis of the state of weather across an entire nation,” Chan wrote in his paper. But it was expensive to send telegrams since companies charged by the word, so codes were developed to condense as much information into as few words as possible.

The challenge was figuring out which code book had been used since, otherwise, it would be nearly impossible to decode the message. Chan perused some 170 telegraphic code books, finally coming across a section about signals used by the US Army Signal Corps that were similar to the pages found in the antique silk dress. Eventually, he realized that the words were codes used by weather stations in the US and Canada to condense telegraph messages about meteorological observations. He relied on old maps to narrow the date to May 27, 1888.

So, for example, “Bismark Omit leafage buck bank” indicates a meteorological reading taken at Bismark station in the Dakota territory. “Omit” means an air temperature of 56° F and pressure of 0.8 inches. “Leafage” translates to a dew point of 32°, recorded at 10 pm. “Buck” meant the weather was clear with no rain and a northerly wind, while “bank” indicates wind speed of 12 mph and a clear sunset.

The identity of the owner of the silk dress remains a question: Who was this mysterious “Bennett”? Over the years, people have suggested the woman was a spy, a trapeze artist, or part of the 19th century “Orphan Trains” that transported children from Eastern to Western cities. Cryptoblogger Nick Pelling speculated that the owner might be one Margaret J. Bennett, a “dowager grande dame of Baltimore society” who died in 1900.

Chan worked through his own reasoning on the topic. Enlisted men typically operated the regular Signal Service weather stations, but other supplementary stations were operated by civilian volunteers, including a number of women. One of those women is listed as Mary C. Bennett in Fairview, Fulton County, Illinois, who would have been 22 in 1888. But it’s a tenuous link, especially since nobody knows when the name tag was attached to the dress. And why would Mary Bennett have sheets of coded meteorological reports in her dress pocket?

Chan considers whether she may have been a telegraph operator, which would explain the reports, but he could find no record that Mary Bennett was ever employed as a telegraph operator, and Fairview was not part of any telegraph circuit used by the Signal Service. Chan concludes that the dress’s owner was possibly another woman who worked as a telegraph operator, probably at the central Signal Service office in Washington, DC—the final destination for such messages.

Cryptologia, 2023. DOI: 10.1080/01611194.2023.2223562 (About DOIs).