DAYTONA BEACH, Fla.—Near-summer temperatures greeted a record crowd at the Daytona International Speedway in Florida last weekend. At the end of each January, the track hosts the Rolex 24, an around-the-clock endurance race that’s now as high-profile as it has ever been during the event’s 62-year history.

Between the packed crowd and the 59-car grid, there’s proof that sports car racing is in good shape. Some of that might be attributable to Drive to Survive‘s rising tide lifting a bunch of non-F1 boats, but there’s more to the story than just a resurgent interest in motorsport. The dramatic-looking GTP prototypes have a lot to do with it—powerful hybrid racing cars from Acura, BMW, Cadillac, and Porsche are bringing in the fans and, in some cases, some pretty famous drivers with F1 or IndyCar wins on their resumes.

But IMSA and the Rolex 24 is about more than just the top class of cars; in addition to the GTP hybrids, the field also comprised the very competitive pro-am LMP2 prototype class and a pair of classes (one for professional teams, another for pro-ams) for production-based machines built to a global set of rules, called GT3. (To be slightly confusing, in IMSA, those classes are known as GTD-Pro and GTD. More on sports car racing being needlessly confusing later.)

There was even a Hollywood megastar in attendance, as the Jerry Bruckheimer-produced, Joseph Kosinski-directed racing movie starring Brad Pitt was at the track filming scenes for the start of that movie.

GTP finds its groove

Last year’s Rolex 24 was the debut of the new GTP cars, and they didn’t have an entirely trouble-free race. These cars are some of the most complicated sports prototypes to turn a wheel due to hybrid systems, and during the 2023 race, two of the entrants required lengthy stops to replace their hybrid batteries. Those teething troubles are a thing of the past, and over the last 12 months, the cars have found an awful lot more speed, with most of the 10-car class breaking Daytona’s lap record during qualifying.

Most of that new speed has come from the teams’ familiarity with the cars after a season of racing but also from a year of software development. Only Porsche’s 963 has had any mechanical upgrades during the off-season. “You… will not notice anything on the outside shell of the car,” explained Urs Kuratle, Porsche Motorsport’s director of factory racing. “So the aerodynamics, all [those] things, they look the same… Sometimes it’s a material change, where a fitting used to be out of aluminum and due to reliability reasons we change to steel or things like this. There are minor details like this.”

This year, the Wayne Taylor Racing team had not one but two ARX-06s. I expected the cars to be front-runners, but a late BoP change added another 40 kg.Jonathan Gitlin

The Cadillacs are fan favorites because of their loud, naturally aspirated V8s. I think the car looks better than the other GTP cars, too.Jonathan Gitlin

Porsche’s 963 is the only GTP car that has had any changes since last year, but they’re all under the bodywork.Jonathan Gitlin

Porsche is the only manufacturer to start selling customer GTP cars so far. The one on the left is the Proton Competition Mustang Sampling car; the one on the right belongs to JDC-Miller MotorSports.Jonathan Gitlin

GTP cars aren’t as fast or even as powerful as an F1 single-seater, but the driver workload from inside the cockpit may be even higher. At last year’s season-ending Petit Le Mans, former F1 champion Jenson Button—then making a guest appearance in the privateer-run JDC Miller Motorsport Porsche 963—came away with a newfound respect for how many different systems could be tweaked from the steering wheel.

“First off, just the braking bias changes—there’s three of them,” said Josef Newgarden, IndyCar champion and Indy 500 winner, who had joined his colleagues at Porsche Penske Motorsport in one of the team’s two 963s. “There’s not one, there’s three, and they can, depending on the traction control side, the engine power side, the differential side—you’ve got all these. And then you’ve got a bunch of other calibration changes that you need to enact for the team in the background. They’re constantly asking you to do something. So you’re very busy in the cockpit.”

The cars have to be driven a little more precisely than, say, Newgarden’s IndyCar, which weighs less and generates more aerodynamic downforce. “You have to respect the limits of this car. It’s actually, I think, easy to overdrive it because it hasn’t got that much downforce; it’s heavier,” Newgarden told me. “The limitations require more respect. So it’s just a different animal than what I’m used to experiencing, but I really enjoy it.”

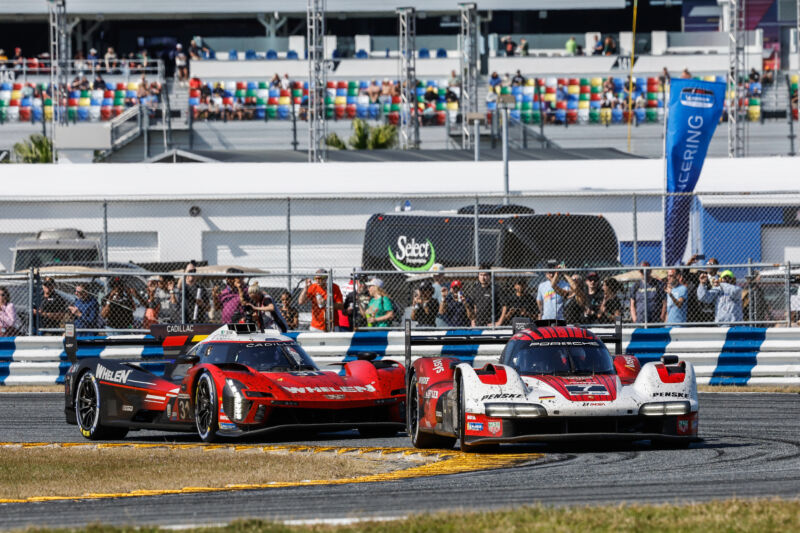

The race in GTP was thrillingly close throughout. Both Porsche Penske cars remained in the fight, as did the customer 963 run by Proton Competition Mustang Sampling, one of the two Cadillac V-Series.Rs (run in this case by Whelen Engineering Cadillac Racing), and one of the two Acura ARX-06s fielded by Wayne Taylor Racing with Andretti (featuring Jenson Button but also IndyCar star Colton Herta driving together with the car’s regular drivers Jordan Taylor and Louis Deletraz).

In fact, thanks to an officiating error, the GTP class only technically raced for 23 hours, 58 minutes, and 25 seconds—the checkered flag was waved a lap too soon (although the rules say that makes it the actual end of the race). After a pretty difficult 2023 season, the #7 Porsche Penske, crewed by Newgarden together with series regulars Dane Cameron, Felipe Nasr, and Matt Campbell, was first across the line, followed seconds later by the Whelen Engineering Cadillac and then the #40 Acura. In total, five cars were still on the lead lap.

There’s more than just GTP

In the past, I have been guilty of focusing on the top class of GTP prototypes when it comes to IMSA racing. In my defense, it’s because the cars are new and look great, and they have generated a lot of fan interest. But the lower categories were no less competitive in this year’s race.

Almost all the entrants in the LMP2 class use identical Oreca machinery—the one outlier was a Ligier recently unearthed from storage, which spent most of its time spinning or crashing, causing multiple safety car periods. Barring that inept performance, the rest of the class was quite evenly matched, with five cars finishing on the same lap and split by less than 20 seconds.

LMP2 is mostly followed by the hardcore fans, but here, too, we saw some familiar names from other series. Former F1 drivers Felipe Massa, Paul di Resta, and F1 reserve driver Pietro Fittipaldi, as well as IndyCar driver and V8 Supercar champion Scott McLaughlin, all raced LMP2 cars at Daytona.

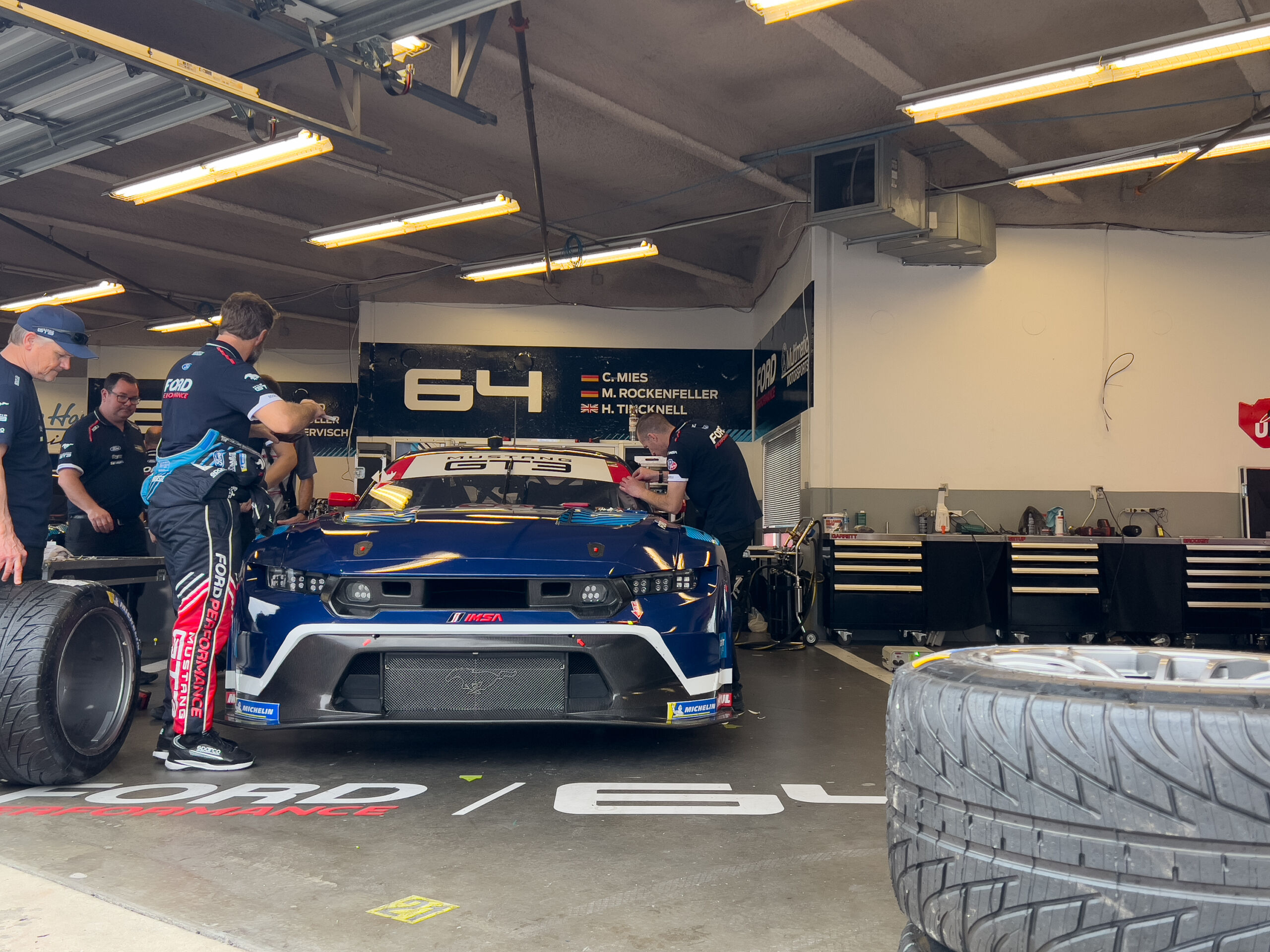

GTD-Pro and GTD help draw the crowd nearly as much as the GTP cars. The global GT3 category has been very successful in creating a relatively level playing field for production-based race cars from the likes of Porsche, Ferrari, BMW, and Lamborghini. This race saw the debut of two new challengers: the new Ford Mustang GT3 and its rival from Detroit, the Chevrolet Corvette Z06 GT3.R.

A few weeks ago, we visited North Carolina for the launch of Ford’s racing season, where we got a good look at the new Mustang racer. The body shell starts off on the normal Mustang production line but from there travels to one of Multimatic’s facilities in Mooresville, where the process of turning it into a GT3 car begins.

The front and rear crash structures are cut away to be replaced by subframes that hold the engine (up front) and transaxle gearbox (at the rear). A hefty roll cage is welded into the car, and it’s clad in lightweight carbon fiber body panels that help the car generate up to 2,000 lbs (900 kg) of downforce.

Compared to the Mustang GT4, which is far closer to a stock Mustang you or I might buy, the GT3 has been designed not just to be fast but also easy to work on for the teams of mechanics that make endurance racing possible.

Ford Performance builds about two Mustang GT3s a month. The engine is enlarged to 5.4 L and set lower down and further back in the chassis.Ford Performance

Here’s one of the two factory Mustang GT3s in its garage before the race.Jonathan Gitlin

Corvette also has a new GT3 car for this year, based on the Z06 version of the mid-engined C8 Corvette.Jonathan Gitlin

The Lexus RC F GT3 is now the oldest GT3 car in the series and was last year’s GTD-Pro winner. This year, both cars were taken out in crashes.Jonathan Gitlin

Rexy the Dinosaur, also known as the #77 AO Racing Porsche 911 GT3 R, is definitely a crowd favorite.Juergen Tap for Porsche Motorsport

“It’s a testament that there are so many manufacturers here doing the same thing in the GTD class, especially with the GT convergence. So there’s been a lot of good racing out there—sometimes too close,” said Mark Rushbrook, global director of Ford Performance, referring to an incident early on in the race where a customer Corvette ran into one of the factory Mustangs, which in turn damaged one of the customer Mustangs—all while the field was behind the safety car.

Drivers in GTD-Pro and GTD aren’t challenging for the overall win, but if anything, they might have a harder job than their peers in the faster GTP cars. That’s because they have to deal with being passed every few laps by the faster machinery while concentrating on their own race. For Ferrari factory driver James Calado, part of the winning Risi Competizione Ferrari 296 GT3 squad, his day job driving the Le Mans-winning Ferrari 499P prototype probably helped.

“I would say that when you’re in the [prototype Ferrari], it’s a little bit less predictable because you’re approaching them a lot quicker. So you need to take a bit of margin, especially with the gentleman drivers,” Calado told me. “But coming back to GT after driving the prototype, you understand why they do what they’re doing because, you know, they’re all professionals. They’re all fast drivers, and they’re all trying to get past as quick as you can. So we make it easy for them. And we also make it easy for us because the idea is that both of us don’t lose time.”

Speaking of that prototype Ferrari, many of us had hoped that the 499P would be entered in IMSA this year, even if just for the longer races. The US is one of Ferrari’s biggest markets, and the convergence of the technical rules between IMSA and the World Endurance Championship (where the 499P competes) should make it relatively easy to bring the car to the North American series. But first, Ferrari would have to send it to be benchmarked at the Windshear wind tunnel in North Carolina, something it has chosen not to do so far. Maybe in 2025?

What’s the point of it all?

Maybe it was the sunshine, maybe it was the noise of the cars, but my time in Daytona had me feeling philosophical about the whole point of the endeavor. All racing series have to balance three competing demands: being a platform for technology development, being a sport, and being entertainment.

As far as technology development goes, there’s quite a lot to go around, even if it’s not at quite the same level as, say, the glory days of the LMP1 hybrids that raced from 2013 to 2017 in the World Endurance Championship. For the GTP cars, the main value to the OEMs that compete, in terms of R&D, mostly comes from software development. This is one of the few areas where teams are allowed a free hand under the rulebook.

For the GTD cars and the even-more production-based cars that race in the Michelin Challenge series (which supports IMSA’s main events, kind of like an opening act), the link is even more direct—the races often come down to fuel strategy, meaning efficient powertrains and aerodynamics bring a competitive advantage.

A technology summit held the day before the Rolex 24 helped elucidate what some of the tech companies that are now showing up as sponsors get out of the sport, too. “I think when we look at motorsports, we tie what we do, technology to motorsports, because there’s a lot of overlap,” said Shawn Henry, chief security officer at Crowdstrike. “From a cybersecurity perspective, it’s about speed. How quickly can you detect something? How quickly can you respond to it? It’s about innovation and vision and teamwork. And we’ve got a really robust program to help them on the sports sector.”

“There is an incredible amount of data, and the IT companies provide tools to turn that data into increased performance,” said Taylor Newill, senior director at Oracle for motorsport technology. “You know, when we look at a tool like AI/ML… nobody’s being replaced here. We are presenting the data in a way that’s easier to analyze for the race engineers, for the drivers, for—if you start to look at marketing—the folks that are figuring out how to engage the fans… Each of the IT tools that are being used are there to help your business run better.”

With regard to the sporting aspect, a lot of that comes down to what’s known as “balance of performance,” or BoP. Plenty of people love to complain about BoP, but it does a good job of equalizing the performance of different makes of car within a class through adding or removing weight and adding or removing power. The closeness of the various classes in qualifying and even the race speaks to the effectiveness of BoP in providing a level playing field.

And finally, racing needs to be entertaining, or no one would bother tuning in. The record crowds we’ve seen since the start of last year speak to this. As does the extremely close racing. The fact that the beginning of the forthcoming Brad Pitt F1 movie (as yet unnamed but due to be released in 2025) is set at the Rolex 24 seems like another vote of approval for the entertainment value of the sport—the production is being advised by sports car veteran Patrick Long, and like the 1971 Steve McQueen movie Le Mans, it will use real race footage as part of the film.

For people watching along at home, that might not have been entirely obvious, unfortunately.

In 2016, I put some noses out of joint at NBC when I timed how much of the network’s F1 broadcasts were taken up by ad breaks and pre-recorded segments. The numbers were bad. NBC lost its F1 coverage to ESPN, which made the smart step of showing the races sans commercials. But NBC carries a lot of US motorsport through its Peacock streaming service, including IndyCar and IMSA racing. And it’s carrying on with its plan to cram as many commercials into races as it can, even for customers paying for an ad-free tier. For a lengthier explanation of just how bad the TV coverage has become, see this piece by Rob Zacny at Remap.

The good news is that IMSA now posts its full races to YouTube a little over a week after they’ve aired—which means you can watch the entire Rolex 24 handily broken up into six-hour chunks: