“I am crying,” Adrienne LaFrance, The Atlantic’s executive editor, said when I connected with her via FaceTime on my Apple Vision Pro. “You look like a computer man.”

What made her choke with laughter was my “persona,” the digital avatar that the device had generated when I had pointed its curved, glass front at my face during setup. I couldn’t see the me that Adrienne saw, but apparently it was uncanny. You look handsome and refined, she told me, but also fake.

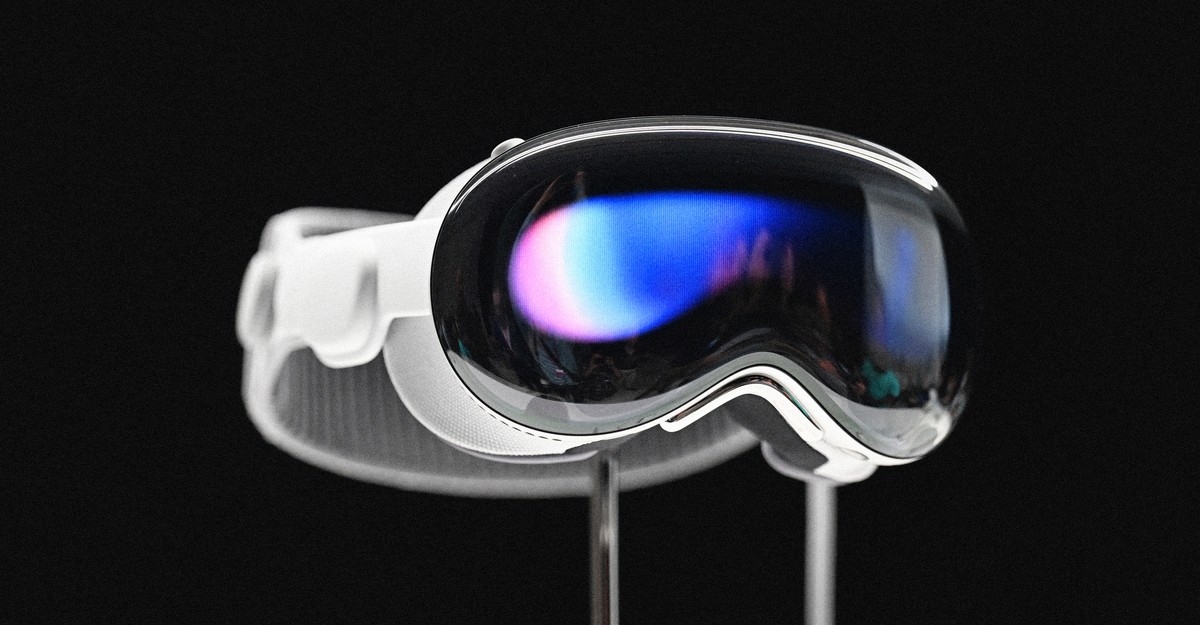

I’d picked up my new face computer hours earlier at the local mall, full of hope for what it would represent. The headset, which weighs as much as a cauliflower and sells for $3,499 and up, is now—after eight months of hype since its announcement—finally available. The Apple Vision Pro offers two innovations in one: a virtual-reality (VR) headset with a higher resolution than most others on the market, and an array of augmented-reality (AR) cameras that allow a wearer to see ordinary computer applications floating in space, and to interact with them via hand gestures. To make the AR work, a knob on the top of the device can dial back your level of “immersion” in a simulated space and replace it with a live video feed of your surroundings, overlaid in real time with computer programs: web browsers, spreadsheets, photo viewers, Disney+. It’s this latter function that most distinguishes the device from other headsets—and from other machines in general. Computers help people work, live, and play, but they also separate us from the world. Apple Vision Pro strives to end that era and inaugurate a new one.

“Maybe if I act like a computer, I will look more normal,” I suggested to Adrienne. When I roboticized my diction, she seemed to think that it helped. I was joking, but then, in a way, I also wasn’t. I did feel like I’d been turned into a robot person of some kind. Is that what the creators of these goggles hoped for, or was it just what I expected? If the Apple Vision Pro wants to reconcile life outside the computer and life within it, the challenge might be insurmountable.

When I placed the Apple Vision Pro on my head and set it up to see the world around me, I found that I was looking out into my living room, across my couches, through the window onto the street, across the craggy winter treetops, and up into the overcast sky. The dual displays, one for each eye, are so sharp and update so quickly that you feel, at first, as though you’re looking at the world as you see it, not how it’s been reconstructed by a headset. At least you feel that way until a row of Apple-app icons materializes in the air in front of you.

The trickery is probably the reason I got physically ill inside the Apple Vision Pro. The round-cornered windows floating above my coffee table looked crisp, but I wasn’t looking only at them. Still feeling stuck in the technological past of earlier in the day, I kept looking down at my phone through the headset. In Apple Vision, the iPhone’s screen was legible but smeared, as if taken from a dream or an AI’s rendering. Checking email seemed impossible, or irritating at the very least; so did sending texts or using Slack. I took a headset screenshot of my view looking at the phone (and at my lap, and at my living room) and sent it to my friends. They egged me on: Get in the car! Go to the grocery store!

Please do not get in the car, or try to operate any other heavy machinery, while wearing the Apple Vision Pro. The device will convince you that you can see areas beyond it, but it renders that space only as trompe l’œil. I had no trouble getting up from the couch to grab my laptop from the other room, but the world jittered in the display, sprouting fuzz around its edges. Objects throbbed in time with my footfalls. Every jostle or cough made reality shudder. This was a rapidly updating computer-desktop-background version of the world, rather than a view of things as they really are.

To stave off this nagging sense of unreality, one can select one of Apple’s built-in “environments”—virtual scenes with animation and sound—that blend in and out of view as you turn the knob on the visor’s top. Using my eyes as a mouse, I selected White Sands, a view of a turbulent sky over the gypsum dunes of southern New Mexico.

It was there, in that Oppenheimer desolation, that I hooked up the goggles to my laptop and cast my Mac display into my augmented reality as a virtual screen. Typing via finger pinches or dictation was a pain, so I used a wireless keyboard. Even that had problems. Touch-typing in that context wasn’t easy, and the writing felt out of phase. The letters on the screen appeared after a very slight delay, just enough to make it feel like my words were being pulled through a wormhole on their way into my document.

I reconnected with Adrienne, via Slack, inside my laptop, through my headset. This is how I’d thought the Apple Vision Pro might best be used—as a virtual office, a place to work that is an actual place and not just a little screen on a table or a desk. The posture benefits were immediate: I was sitting upright, my back against a cushion, my head straight, my eyes focused on the horizon (and the future?). I felt like an illustration in a workplace-ergonomics poster. I felt good.

But also disoriented. Before linking to my laptop, I’d already opened Microsoft Word, and now I couldn’t find that window. It was stuck, somewhere in virtual space, in another room of my house. Looking side to side, I finally saw the foreshortened sliver of my document in the living-room doorway. I tried to pinch it, but couldn’t quite reach. So I opened Word anew, on my laptop, in my headset. Now I began to feel afraid, like I’d gone so deep inside computerspace that I would never get out again. Thunder clapped in my ears from the background environment. I was alone in the wilderness, in the goggles wrapped around my head.

Maybe the White Sands thunderhead was too foreboding. A storm above a desert—that was the last thing I needed while I felt like I was drowning. So I switched myself into the Mount Hood environment, with its lakeside vista, lined in evergreens, and its gentle chirp of birds. It helped. Light glinted across the water next to a window bearing text messages from my family. But then a clang and a notice interrupted my newfound peace: 20 percent battery remaining. I had to plug in my peaceful, lakefront office to recharge it.

I tried to keep my struggles (and my nausea) in perspective. These may be nothing more than growing pains for this new paradigm for computing. The original Macintosh was only marginally useful, and the first iPhone didn’t do that much. So I settled back into Word in space, tapping out a portion of this article while the experience was fresh. A reality-affirming rocky shore with proud trees filled my peripheral vision. Eventually, I heard the sounds of my wife and daughter coming back into the house. When I dialed back into reality, or the rendered version of the world around me, I found my wife was just steps away from my head, pointing her phone camera to record me, the computer man.

It had become dark outside since I’d pulled Mount Hood over my head. I tried to scratch my brow but a face computer stood in the way. I was more off-kilter than expected. Augmented reality is supposed to increase your sense of place compared with VR, but I’ve tried the older, lower-resolution options—the Meta Quest, the HTC Vive—and the Apple Vision Pro made me feel even more decoupled from the world.

I removed the goggles and tried to recombobulate. Inexplicably starving, I walked toward the kitchen, headset-free, past the place where, in the Apple Vision Pro dimension, I’d left my document. I began devouring Tostitos, as if to reaffirm my corporeal existence. My wife tried to tell me about her day, our daughter’s fiddle lesson, the dog she’d nearly hit with the car. But I couldn’t listen. I felt agitated. She had no idea what had just happened to me. If someone had just come back from outer space or a deep-sea submarine, you wouldn’t expect them to make small talk.

When my head and spleen had been restored, I returned to the Apple Vision Pro. This time I’d try it out as a media device rather than a general-purpose computer. Watching movies—I chose Avatar: The Way of Water, for obvious reasons—is spectacular, so long as you can tolerate the headset’s weight on your face for hours. It’s like watching the biggest, brightest television you’ve ever seen, at the proper distance, in a dark room. Games have promise, too: An AR version of Fruit Ninja dumped cartoonish orange and watermelon juices onto my carpet. I had trouble getting the game to recognize my hand movements, but it felt like the special, physical experience you’d have at an arcade. And an Apple TV+ show called Adventure put me on a tightrope high over a Norwegian fjord with the highliner Faith Dickey. The company has branded such content as Apple Immersive Video, a combination of 3-D, 8K resolution, and spatial sound. It was the sharpest, most eye-watering film I’ve ever seen, but it also felt a little corny, like a tech-demo nature show playing at Best Buy. I’ve pursued such thrills in the past only to abandon them in favor of watching YouTube on an iPhone six inches from my face in bed.

You can also capture what you see inside the headset and save it as a still or moving image. In Apple’s marketing and in Apple Vision Pro reviews, these “spatial” recordings have been sold as a way to relive your past—children feature prominently. I found these videos neither immersive nor crisp. With edges that blend into the background, they come off like a gesture toward the past, one that amplifies the tender, connotative feelings of a moment, but that may not quite convey what really happened. I can’t tell if that will give us stronger memories, or just more saccharin ones. (Or maybe, as Kathryn Bigelow’s cyberpunk film, Strange Days, predicted in 1995, spatial videos will just end up as a more visceral way to consume violence and pornography.)

The idea that family videos might be made into more perfect stand-ins for our lived experience suggests the grander Apple vision. With the release of this device, the company is trying to reconcile, once and for all, the digital and physical worlds. Apple has probably done enough, even in this early iteration, to convince many users that such a bridge can and will be built. The device is incredible already, and Apple may yet resolve the quirks that troubled me. (I may yet become accustomed to them, too.)

But what if the chasm that Apple means to span represents a fundamental limit to technology? For a time, at what may have been the height of the internet’s thrall, it became popular to pretend that the digital and material worlds were continuous—that the “real” one had no special meaning, because cyberspace had become a part of it. That turned out to be wrong. We live in cars and on couches and, separately, we also live on phones. Apple believes it can resolve this conflict—that the digital and material worlds can be merged together—but it has only put the conflict into higher resolution. A headset is a pair of spectacles, but a headset is also a blindfold.