Listen to this article

Listen to more stories on curio

The next Bond movie should be called Libido of Secrecy. It should be called Marmalizer, Mercuryface, Die to Tell the Tale.

Actually—and I’m quite serious—it should be called The Black Daffodil, after Ian Fleming’s only book of poetry. Nicholas Shakespeare, in his walloping new biography, Ian Fleming: The Complete Man, describes this slim volume, bound in black and self-published in 1928, as “the holy grail for Fleming collectors.” He was 20. He was arty. Shakespeare includes a contemporary sample from Fleming’s journal: “If the wages of sin are Death / I am willing to pay / I have had my short spasm of life / now let death take its sway.” We have to rely on the sample, because The Black Daffodil itself is gone. “He read me several poems,” Fleming’s friend and sometime business partner Ivar Bryce remembered, “the beauty of which moved me deeply.” But then something went wrong, or some other presence moved in. “He took every copy that had been printed,” Bryce continued, “and consigned the whole edition pitilessly to the flames.”

Rather Bondlike, that “pitilessly.” Bondlike, too, is the “short spasm of life” in the little poem. In fact, although he wouldn’t be born for another 24 years, if you squint at the Black Daffodil episode, at this tiny debacle in the artistic life of Ian Fleming, you can indeed make out the wriggling germ of James Bond.

Fleming worried that his youthful verses “aped Rupert Brooke,” the golden young man who wrote “The Soldier” in 1914 and who probably would have been killed at Gallipoli had he not been carried off en route by an infected mosquito bite: “If I should die, think only this of me: / That there’s some corner of a foreign field / That is for ever England.” And isn’t there a corner of James Bond that vibrates forever with this perfumed, Georgian strain of romantic English fatalism and mystical chauvinism? Although routed now through the circuits of a sleek 20th-century killing machine. A killing-and-shagging machine, who likes scrambled eggs for breakfast and smokes fancy-pants blended cigarettes. Maybe we can put it like this: Ian Fleming wrote the poetry, and James Bond—that bastard, that black daffodil—burned it.

As he sprang from his author’s head in the early months of 1952, with a .25 Beretta in his left armpit, Bond was in many ways a product of psychic necessity. Fleming—in his mid-40s, and against everybody’s advice—was about to get married. His bride, Ann Charteris, was aristocratic and reckless. “We are, of course, totally unsuited,” Fleming wrote to his new brother-in-law. “I’m a non-communicator, a symmetrist, of a bilious and melancholic temperament … Ann is a sanguine anarchist/traditionalist. So china will fly, and there will be rage and tears.” On the morning of the wedding, which was held down the road from Fleming’s Goldeneye estate in Jamaica, the happy couple were jarred awake by the croaking of an unknown bird. Doom! He had already finished the first draft of Casino Royale.

He was quite an interesting man, Ian Fleming. Born into great wealth and great expectations, he sequentially disgraced himself at Eton (general loucheness) and Sandhurst (gonorrhea), clanging about in the shadow of his older brother, Peter, an acclaimed author-adventurer. His father had been killed in the First World War; his mother was a nightmare. Redeemed by a spell at a private educational establishment in the Austrian Alps, where he was introduced to the work of the psychologist Alfred Adler (he took the Adlerian concept of the inferiority complex very much to heart), he returned strengthened to the world. The Foreign Office didn’t want him, but journalism did: Shakespeare’s account of the Stalinist show trial of six British engineers, which Fleming covered in Moscow in 1933 for Reuters, is riveting.

And he had an interesting war. The weird thing about the Bond books (it may be their secret) is that they read like the work of a gifted and faintly sociopathic fantasist-researcher—somebody with no actual experience of espionage, geopolitics, money, travel, fighting, or, indeed, humans. In fact, Fleming was worldly to a degree and, if anything, overqualified to write spy novels. From the late 1930s to 1945, he worked at the top levels of Naval Intelligence, liaising between the Admiralty and Downing Street, and was closely involved with—among other things—operational planning and target selection for two elite intelligence-gathering units: 30AU and T-Force. These were his glory days. Shakespeare uses the journalist Alan Moorehead’s line about soldiers at war to describe Fleming: “He was, for a moment of time, a complete man, and he had this sublimity in him.”

But now it was the ’50s, and that was all over. The empire was suffering postwar contractions, and Fleming was no longer running his quasi-private armies. And at Goldeneye, he faced the shutdown of decades of swinging bachelordom. “I was in a terrible state,” he explained to his confidant Maud Russell, “& appalled at the thought of getting married. I sat down at the typewriter …”

Casino Royale is an odd book: oddly written, oddly paced, and suffused with an obsessive, almost sickly sensuality. “He watched carefully as the deep glass became frosted with the pale golden drink, slightly aerated by the bruising of the shaker.” The action is mostly bungled—until the famous torture scene, when Bond gets his “underpart” flogged with a carpet beater and the prose snaps into rapturous focus. “Bond’s flesh cringed as the cane surface just touched him.” (Fleming and Ann liked whipping each other.)

And Bond is an odd character, an odd and very modern hero. An automaton and a sybarite. He is mentally efficient, almost clinically so, with an emptiness of head that anticipates Jack Reacher: “He closed his eyes and his thoughts pursued his imagination through a series of carefully constructed scenes as if he was watching the tumbling chips of coloured glass in a kaleidoscope.” But he’s also extremely fussy, American Psycho–style—about drinks, cars, what to wear in bed. “Bond had always disliked pyjamas and had slept naked until in Hong Kong at the end of the war he came across the perfect compromise. This was a pyjama-coat which came almost down to the knees.” (Detailed description of the pyjama-coat follows.)

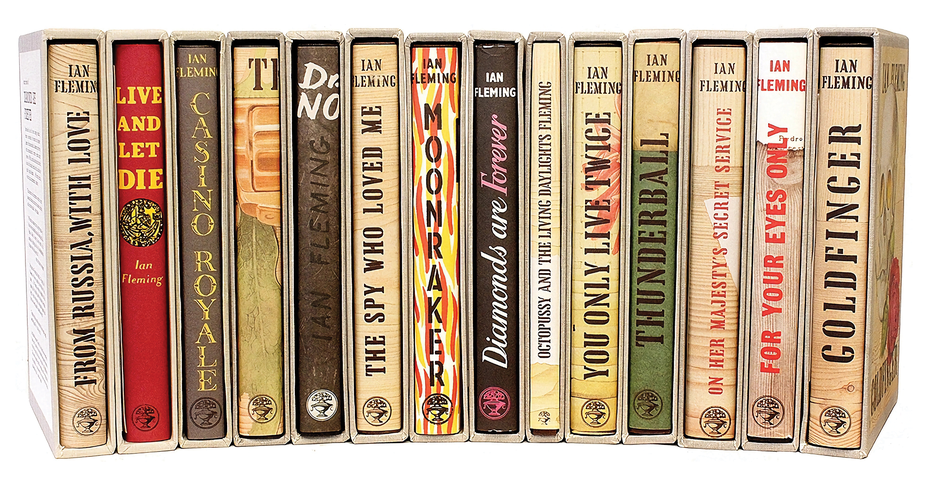

The point is that all the elements—the nastiness, the daintiness, the vacancy, the improbability, and the creepy voluptuousness—were present from the beginning, and it wouldn’t take long for Fleming to perfect the mixture (1957’s From Russia, With Love, for example, is an excellent read). The writing mostly got done at Goldeneye, at high speed, sometimes on a gold-plated typewriter. From Jamaica, he would send his manuscripts to his friend Clare Blanchard in New York. Blanchard, a devout Catholic, was always appalled: “The only explanation I have,” she says in Ian Fleming, “is that he wrote [the books] uninhibitedly and that the forces of evil … came through them as water comes through a tap.”

Fame as the creator of James Bond, in combination with his old elite connections, would project Fleming back into the center of events. Senator John F. Kennedy, a huge fan, sought his counsel about Cuba. Massive success was Fleming’s at last. But the black daffodil was upon him. By 1960, he was sick of Bond and wondering how he could kill him off. “How the keys creak as I type,” he complained in a letter to the novelist William Plomer. Bond, however, “was as impervious to death as was Dracula,” Shakespeare writes. The last chapters of Ian Fleming are dark, Bond taking over the world as his creator staggers through heart attacks toward a premature death. Fleming succumbed at age 56: The short spasm, shortened further by 70 cigarettes a day and lashings of booze, was over. The journalist Malcolm Muggeridge, writing in 1966 to Fleming’s first biographer, John Pearson, had a warning: “Don’t you get destroyed by Bond’s ghost as Ian did by his creation. Remember, he’s the Devil.”

This article appears in the March 2024 print edition with the headline “The James Bond Trap.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.