For the past decade, one of the most linguistically diverse places in the world, square mile after square mile, has been my home: Queens, New York. The soundtrack outside my door is extraordinary: On any given block, passing voices speak varieties of Polish, Ukrainian, Egyptian Arabic, Mexican Spanish, Puerto Rican Spanish, Dominican Spanish, Ecuadorian Spanish, Kichwa, and all the forms of New York City English they give rise to. As a linguist, I can usually distinguish them from one another, but understand only a fraction of what people are saying.

In my neighborhood, like in many other working-class immigrant neighborhoods in the city’s outer boroughs, hundreds of language groups from around the world have carved out entire communities. Users of Seke, a language from five villages in Nepal with 700 speakers, live a subway ride away. In certain stores, Albanians, Bosnians, Serbs, and Montenegrins all reunite, deploying the languages of the former Yugoslavia as if the country still existed. An old Macedonian selling tchotchkes from a table on the street is a gentle bully in every language he speaks. No group has a majority, or even 15 percent of the neighborhood, and most are at just 5 or 10 percent. English acts, for the most part, as a vital lingua franca, not a linguistic bulldozer. This last point is crucial, because a city can be a haven for diversity but also an end point, metabolizing the languages and cultures of the world until none is left.

Every group of speakers in these neighborhoods seems to have its clubs, some more private and intimidating than others. At Club Trentino, old ladies making doilies hold a halting conversation in Nones, a Romance language with similarities to Ladin, Lombard, and Venetian. Gottscheer Hall is the focal point and community hub for an estimated 18,000 Gottscheers and their descendants in the New York area. While now also hosting quinceañeras and house-music parties, and doubling as a neighborhood bar, it’s still the headquarters for all things Gottscheer: the Blau Weiss soccer team, the annual Miss Gottscheer contest, the Relief Association, multiple choral groups, and the annual Bauernball (“Farmers’ Ball”), among other community institutions. This is the last outpost for Gottscheerish, an endangered Germanic language that developed in the isolation of the Gottschee (Kočevje) region in what is now Slovenia. Its speakers packed up seven centuries of history when they fled in 1944 and 1945, escaping via displaced-persons camps to Germany and Austria, where people largely assimilated, or else here to Queens, where the last speakers live. At the Gottscheer-owned pork store nearby, a placard behind the hanging sausages says We speak in 14 languages, and that’s not even counting Gottscheerish.

My neighborhood has its signature sound, but there are several dozen others that are just as diverse, each in a different way. These are the places where the Endangered Language Alliance, the nonprofit I co-direct, has recorded New Yorkers speaking more than 100 languages that the census and other data sets say don’t officially exist, and more than 700 in total. That linguistic portrait makes clear that early–21st-century New York City is a last, improbable refuge for embattled and endangered languages—ones that are being hounded out of existence elsewhere. And this deep linguistic diversity is among the least explored but possibly most consequential factors in New York’s history and makeup: The disproportionate presence of historically oppressed and marginalized groups speaking smaller languages quietly informs much of the city’s distinctive politics, culture, and economy. Its soul can be found in the existence of these many, many languages, explaining New York’s particular capacity for tolerance and its ability to “make room” for others, however fraught and grudging.

But this diversity is not to be taken for granted. The powerful, by conquest or commerce or culture or creed, have historically stamped out and stigmatized the languages of the powerless. My multilingual neighborhood uses English as a bridge for communication, but this arrangement is not the case in many other places. Languages today are not “dying natural deaths” or simply evolving into new forms. Now more than ever, languages are being pushed out of usage. Without continuous infusions of new speakers, few immigrant languages typically make it beyond the third generation. Threats to immigration and immigrant lives, language loss in the homelands, and the gentrification of cities appear to be accelerating the cycle. New York is no exception.

The U.S. census first inquired about language in 1890, and since then, the way it has asked has been too limited to reflect the complex dynamics of migration and cultural change—which has ensured that Indigenous, minority, and primarily oral languages are systematically undercounted. But ELA’s count makes clear that one out of every 10 languages on the planet, including just about all the sizable ones, has at least a single speaker in New York. Hundreds of languages have substantial communities of hundreds if not thousands of speakers, though the reliability of community estimates varies. Nearly 40 percent of the city’s languages are from Asia, a quarter are from Africa, and just under 20 percent each are from Europe and the Americas, with a much smaller number from Oceania and the Pacific. We can say definitively that these largely overlooked languages actually constitute the majority of the city’s mother tongues. They are not exotic; they are integral. If not always individually, in aggregate they are a force.

New York’s undersung linguistic richness matters for profoundly practical reasons—because children learn best in their first language, and because of a whole host of positive effects on physical and mental health that come from native languages remaining strong. There is much knowledge, wisdom, and art contained in every single language, which no amount of last-minute translation can salvage. Languages are crucial to our understanding of human expression and communication in general; the least-known vernaculars are often the ones that prove that a certain sound, feature, or meaning is even possible.

The archetypal New Yorker is neither an artist nor an actor nor a banker, but a working-class, multilingual immigrant. Close to 40 percent of New Yorkers were born in another country, a figure that is only slightly lower than it was a century ago. Numerically, they form the largest foreign-born population of any metropolitan area in the world. About half of all New Yorkers speak a language other than English at home, and many of the rest have non-English-speaking parents or grandparents. With few exceptions, linguistic, religious, ethnic, and other minorities have been overrepresented in diasporas in comparison to their home countries, because they are the ones hit hardest by conflict and thus impelled to leave. The pressures of migration mean that smaller languages will have to survive in urban environments if they are going to survive at all.

As a repository of language, New York is nowhere near utopia. But it could be almost like a modern Babel—not the one from the biblical myth, cursed and divided by mutual unintelligibility, nor a “Babel in reverse” that steamrolls languages into a single tongue, but one where hundreds of languages thrive in a diverse network. Could there be a version of the city in which English, Chinese, Spanish, and other widely spoken languages are useful tools for mutually intelligible conversation, not killer languages whose speakers assume their speech is superior? In this imaginary—but not impossible—New York, it would be a place where vastly different languages would be recognized, interpreted, and enjoyed, not wished away or weeded out.

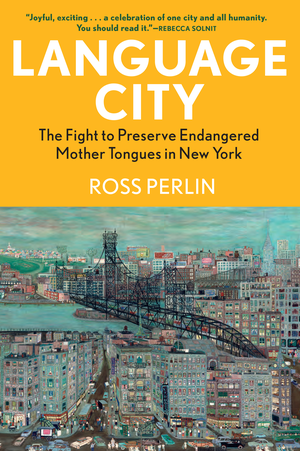

This article has been excerpted from Ross Perlin’s new book, Language City.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.