Listen to this article

Listen to more stories on curio

If you do not have a child under the age of 16, or are not yourself under the age of 16, you might have no idea who Raina is. So it was with me. I called a friend with kids and said, “Have you heard of an author named Raina Telgemeier?”

“Of course,” she said, sounding bemused, as if I’d asked whether she was familiar with the automobile.

“Like the Beatles for children,” another parent friend explained.

Last spring, standing in the theater at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum in Columbus, Ohio, surveying the hundreds of kids and teenagers who had come to meet Raina, I realized the scale of my ignorance. Half an hour earlier, her fans had been standing on their seats, jumping up and down, waving their arms in the air, but now the long wait for autographs had begun. Everyone had been assigned a number and organized into subgroups so they could approach the signing table in shifts. Nobody seemed to mind especially—many were plunked down on the floor, contentedly rereading her books, as an hour passed, then an hour and a half.

One mother and her 8-year-old daughter had come from Philadelphia. Another family had driven up from Tennessee. “We would go anywhere to see Raina,” one parent said.

“The magic of Raina is real,” confirmed a school librarian who’d brought her daughter to meet Telgemeier here, at a public event celebrating the author’s first retrospective. Every spring, the librarian told me, she runs a report to determine which of the library’s books have been checked out the most. It was June, so she could share that, once again, “four out of the top five are Raina books. Children reread those books over and over and over.”

Telgemeier, a smiley yet somewhat shy 46-year-old with glasses and dangly earrings, has almost accustomed herself to being known mononymically, like Cher. She has boxes and boxes of fan mail in her basement, more than she can open, and there are boxes more at her publisher’s offices in New York. It’s wonderful, she told me, and unnerving. She got her break in her mid-20s, when Scholastic commissioned her to create graphic-novel adaptations of books from The Baby-Sitters Club series. Her editor took an interest in a web comic she was self-publishing at the time, which became her first graphic memoir, Smile. Scholastic published the book in 2010 as a kind of experiment. At the time, the market for middle-grade comics was dominated by superheroes and fantasy. Would kids want a nonfiction comic about a normal sixth-grade girl’s tricky journey with braces? Publishing executives had doubts about whether enough girls could be persuaded to read comics at all. (It was assumed that a comic with a girl protagonist would require an audience of girls.)

Smile’s first print run sold out in four months, and the book spent 240 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list. In 2014, Telgemeier published Sisters, and in 2019, Guts. This trio of graphic memoirs has made her, like Roald Dahl and Judy Blume, the kind of author who defines a generation of children’s literature, and whose books, in turn, have helped define a generation’s experience of childhood.

Telgemeier’s books are well plotted, heartfelt, and beautifully drawn. She has a keen eye for the texture of kid life. In Smile, she devotes an entire page to the frantic and cruddy work of cleaning a retainer in a school bathroom after eating an ill-advised peanut-butter sandwich—and the satisfying click of popping it back into place. But what set her books apart are her vivid, candid portraits of her childhood angst: her orthodontia-induced shame; her growing awareness of her parents’ fractious marriage; the serious anxiety disorder that emerged when she was in elementary school.

The popularity of these books has overlapped with years during which clinical anxiety among American children and adolescents has reached new heights—so much so that multiple organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, noting a rise in depression too, declared a state of emergency in 2021. Telgemeier’s success—she’s sold more than 10 million books in the United States alone, according to Circana BookScan—is driven by her ability to describe experiences that many kids struggle to articulate and feel powerless to change.

The story of Telgemeier’s career is also the story of a transformation of the children’s-book industry. Graphic novels now have their own shelves in the kids’ section of many bookstores. A group of cartoonists—Kayla Miller, Jerry Craft, Betty C. Tang—has made hits in the pattern of Smile and Guts, about awkward crushes and first-day-of-school nerves and wobbly friendships. The superhero has been joined in the comic-book canon by another archetype: the anxious kid.

From the time she could hold a crayon, Telgemeier, who grew up in San Francisco, began and ended every day by drawing. Her parents set up her bedroom with a table and an array of art supplies; next to the table was a little record player. She would wake up in the morning and go straight to her table, put on her headphones, and draw, Telgemeier’s mother, Sue, told me.

At one point, when Raina was 3 or 4, Sue decided to surprise her by turning the drawings into a child-size quilt. Sue took white fabric and cut it into squares, then traced the drawings she found especially interesting in fabric paints and stitched over them in the right colors. But when Raina saw the finished quilt, she backed away whimpering. She wouldn’t touch it.

“It was a while later before I understood what had happened,” Sue said. “Raina had been drawing her nightmares. And the best artworks were her nightmares, her monsters.” Telgemeier had never mentioned the nightmares aloud, Sue said. “She would draw it and then it would get put away.”

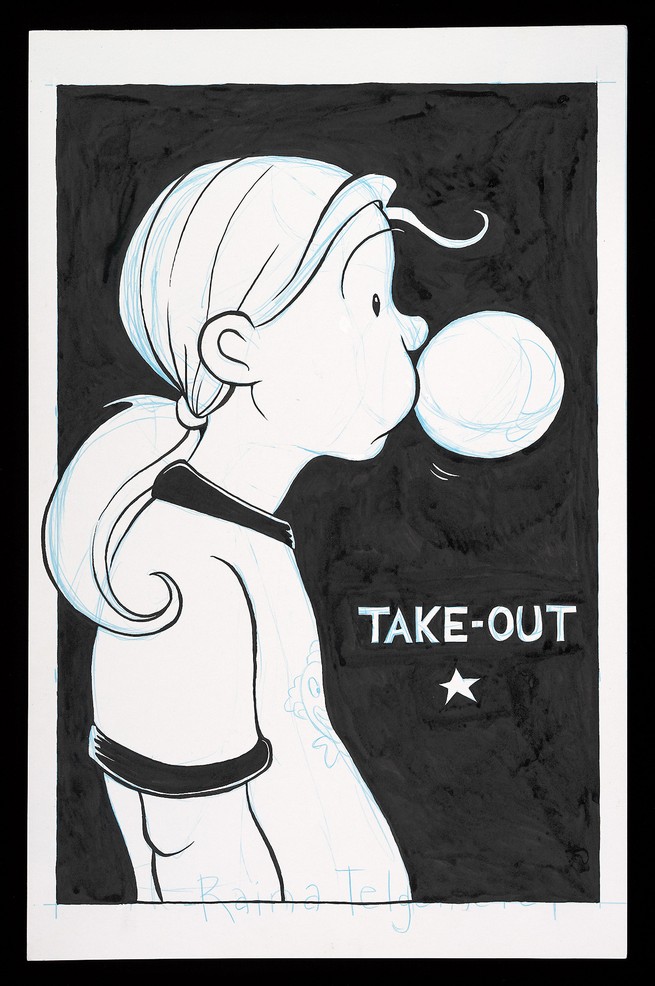

Telgemeier has never stopped drawing her monsters. All through grade school, middle school, and high school, she’d sit down in the afternoon and draw what had happened that day, sometimes amending what she had actually said into what she wished she’d said. In 1999, at 22, she left San Francisco to attend the School of Visual Arts in New York, where she started a minicomic (the comic equivalent of a zine) called Take-Out, full of short pieces about her childhood as well as her 20-something life: squabbling with roommates, struggling to get out the door on a bad hair day, scrounging under the bed for change to buy a $1.25 slice of pizza.

Take-Out was self-published. Telgemeier made copies herself and sold them at comics fairs. She noticed that the comics that received the most positive feedback featured her childhood. Over time, kid Raina became the star of Telgemeier’s work. Her comics articulate the emotions of childhood with an intensity faithful to reality: the high highs of being included in a middle-school sleepover; the queasy low of realizing that your friends are playing a mean practical joke on you at the sleepover.

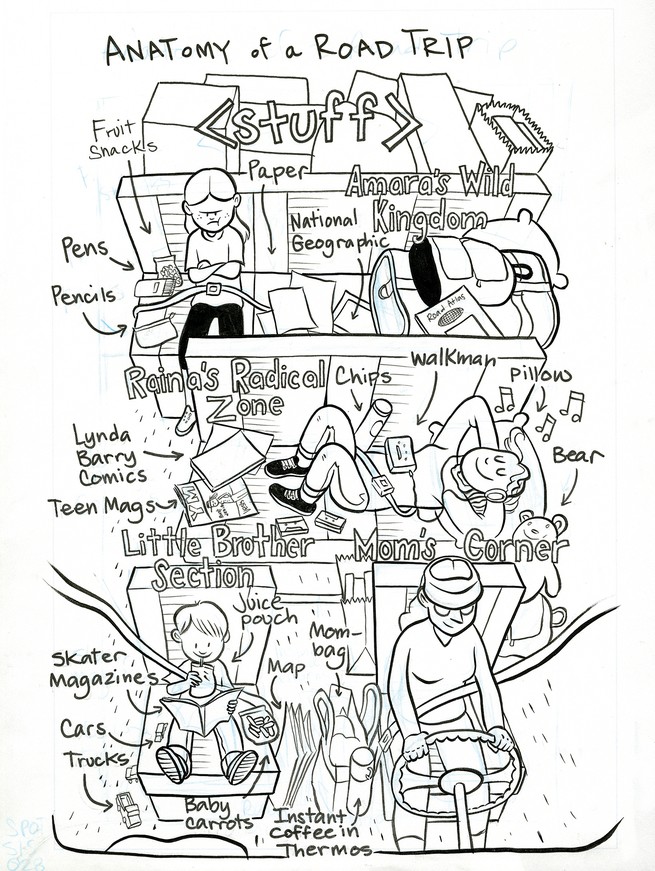

The books that made her famous recount the worst, most miserable moments of her young life in painful detail. Smile begins with an accident: In sixth grade, she fell on her face while running with her friends, knocking one front tooth out entirely and jamming the other so far into her gums that it took years of excruciating orthodontia to give her a normal-looking mouth. Sisters scrutinizes her fraught childhood relationship with her younger sister, Amara, and tells the story of a long road trip she took with her mom and younger siblings shadowed by the realization that her parents were considering separating. (Sue and Denis Telgemeier eventually divorced.) In Guts, 9-year-old Raina develops debilitating anxiety—in particular, a fear of throwing up.

I had been skeptical, at first, that a graphic novel for elementary and middle schoolers could approach the topic of mental illness without sugarcoating or melodramatizing it. But reading Guts, I recognized why Telgemeier’s books command such loyalty. The book devotes whole pages to her panic attacks: the feeling that she’s frozen, falling down and down and down. As someone who also had anxious middle- and high-school years, I was especially struck by one panel, placed in a scene where Raina sees that one of her friends and classmates has had to rush to the bathroom in the middle of class. Raina’s anxiety spikes. Is Jane throwing up? They’d shared lunch! The panel shows Raina caught in ripples of sickening green that radiate outward from her head to fill the whole frame. Her teeth are gritted; her hands grip her hair tightly, but a curl escapes. Her own thought balloons swim around her, choking off any view of where she is or whom she’s with. “What if I’m next?” one reads. The next three, swelling in size: “What if? WHAT IF? WHAT IF!?”

I’m transfixed by this frame—the pea-green energy waves, the choking thought bubbles, the feeling that the room has faded away until the only thing left is WHAT IF? This is exactly what it’s like.

“I think probably the most important contribution to comic storytelling that Raina has pioneered is the notion of emotion as action,” says Scott McCloud, a cartoonist who wrote the landmark book Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. Telgemeier studied McCloud’s books when she was a teen; now they are friends and collaborators. “This is something that my generation of superhero cartoonists didn’t fully understand,” McCloud told me. “I mean, emotion was something that you crammed into a word balloon while people were fighting each other. But in Raina’s case, there’s a small difference in a line showing that, let’s say, a smile is beginning to disappear. A bit of anxiety is creeping into an expression … And Raina understands that each of those deserves its own panel.”

McCloud said he’s fascinated by a moment in Telgemeier’s graphic novel Drama, loosely based on her time doing theater in high school. (In addition to her memoirs, and her work on the first four volumes of the graphic Baby-Sitters Club series, Telgemeier has written and illustrated two graphic novels.) The protagonist, Callie, is looking for the boy she’s recently kissed for the first time, but he’s told his brother to tell her that he can’t walk her home after school because of baseball practice. Here, Telgemeier draws an entire spread with no words. The left-hand page has three frames: Callie running out of the school doors, looking concerned; Callie arriving at a chain-link fence, a little puff of her breath condensing in the chilly air around her; Callie’s face seen through the chain link, eyes wide. The right-hand page pulls back to show the whole diamond and a stand of trees beyond it. Callie, looking small, is clutching the fence with both hands. She’s alone; the field is empty. Her crush lied about baseball practice.

“You know, from a superhero-artist standpoint, nothing is happening,” McCloud told me. “But from the standpoint of a middle-school kid feeling one of those first moments of disappointment and abandonment, everything is happening, and it deserves that full page.”

“I call this the cozy nerd house,” Telgemeier told me, handing me a blanket and a cup of tea. She lives in a quiet, spacious trilevel 45 minutes east of San Francisco. It’s woodsy out there, with citrus trees, old oaks, and long driveways. In her living room, we each settled into a corner of her plush, oversize sectional with cups of tea, and a cat came to sit on my lap.

“I think what I wanted more than anything was a house,” Telgemeier told me. “From the time I was a small child: Someday, I’ll have a house with a backyard.”

The problem of domestic space features prominently in Telgemeier’s memoirs. I’d seen where she grew up, or at least the comics version, in Sisters: a San Francisco apartment with two bedrooms and a single bathroom. Perfectly nice, but not roomy for a family of five. In Guts, Raina’s anxiety seems related to, or at least exacerbated by, the fact that she struggles to get her own space at home. Her toddler brother catches a stomach flu, and Raina, panicked that she’ll catch it, begs her mom to let her sleep outside. No dice. In Sisters, Amara plays records over and over in their shared room when Raina wants silence. Raina is afraid of snakes; Amara gets a pet snake. Raina loves to draw; Amara does too. “She very quickly eclipsed me,” Telgemeier told me. “Her 2-year-old drawings and my 7-year-old drawings were almost on par.” Young Raina navigates the tension between her desire to feel loved by and connected to others and her craving for privacy—she needs space away from people to feel her big feelings and to process them into art.

These days, Telgemeier’s inclination toward quiet and privacy can be confounded by her professional ambitions. She never expected to have the profile she now does. The release of Sisters, in 2014, marked a turning point: She went from being a successful author to something more like an icon. “That was when, like, I became ‘Raina,’ ” Telgemeier said. “They made a poster of my face that said Raina’s back.” Her eyes went wide, as if she was overwhelmed and incredulous just at the memory of it.

Telgemeier now represented two people: herself, the adult with the career and retirement savings, and Raina, the kid in her memoirs. This version of who she used to be remains alive and vivid to millions of people—more real, in some ways, than her adult self is. “It’s like suddenly I was the main character of a book and I’m the writer of the book and I’m a real person.” She sensed that fans now met her and reeled at the possibility of encountering, in one person, their fictional best friend and their favorite author. “I was standing on stages and people were just interested in me—the character, the author, the everything.” This kind of fame can strain. A number of Raina’s family members and friends felt uncomfortable with having their real lives depicted in books that now had an audience of millions. Telgemeier had been thoughtful about how publishing might affect her relationships before—she’d shown Sisters to Amara in advance, for example—but she became more protective as curiosity grew, and more cautious about hurting people close to her.

Before Sisters, Telgemeier had been used to attending comic-cons and festivals alongside her indie cartoonist friends, selling her work copy by copy, but now she was managed by Scholastic, taking pictures with hundreds of kids at ticketed events. The emetophobia and fear of illness that Raina develops in Guts were the beginning of an anxiety disorder that Telgemeier continues to manage. Despite having real affection for her fans, she finds touring challenging—being around crowds of germy kids, flying on airplanes, using strange bathrooms. She started going to therapy in elementary school, an experience she depicts in Guts, then stopped by middle school, but she went back shortly after the publication of Sisters; her anxiety was making it difficult for her to leave the house or sleep through the night. One of the primary reasons she decided not to have children, she told me, was that she wasn’t up for morning sickness. Her career and her anxiety took a toll on her marriage to the cartoonist Dave Roman; the two divorced in 2015.

When the pandemic hit, Telgemeier found herself home alone, not traveling for the first time in recent memory. Social distancing came easily to her—she’d been doing it for years during flu season. “Because I wasn’t seeing other people, it completely removed the part of my brain that was always worrying: Hmm. Was that person sneezing? Was that person coughing? Did I touch somebody at the grocery store? … It was one of the best experiences of my life.”

Nowadays, she is back on the road. Telgemeier is enthusiastic in her interactions with the people who stand in line to talk with her, though I noticed that her signing tables were arranged to ensure that a few feet remained between her and her fans. In Columbus, people were instructed to remain on the opposite side of the table, even for photographs.

The most common question children ask her at public appearances is “Did this really happen?” Telgemeier tries to head off this line of inquiry by making a blanket statement: Yes, she announces cheerfully. These books are based on my life, which means that everything that happens in the books really happened to me. We really had a pet snake. I really did lose my two front teeth. If it’s in the book, it really happened. The questions tend to continue anyway.

Telgemeier isn’t surprised by this, she told me. Kids have a reasonable impulse when confronted with the middle-aged author—great teeth, smiling, famous—to double-check that she went through everything young Raina did, the indignities and fears and crises they themselves experience.

I understand wanting that kind of reassurance. I had my first panic attack when I was 11 or 12 and had absolutely no idea what was happening—at the time, none of the books aimed at my age group dealt with this stuff, at least none that I saw, and so I worried that there must be something terribly wrong with me; that I might be uniquely doomed to an unhappy, lonely life. Telgemeier’s books offer an antidote to that kind of isolation. By making anxiety the obstacle faced by a compelling, sympathetic hero, these books reveal the possibility that a reader with her own psychological struggles—panic attacks or emetophobia or hair pulling or big sadness—might wind up okay, or even great.

“I wish I’d had that,” I told Telgemeier over tea in her living room.

“I know,” she said, half-smiling. “I wish I’d had it too.”

After we finished our tea, Telgemeier took me upstairs to see her studio, and then downstairs, where she stores her archives: all of her old journals, childhood sketches, costumes she made for school plays, pen cases, favorite markers, photographs, stuffed animals. A piece of paper upon which her first-grade teacher had written, “Dear Raina, What is the baby’s name? Do you help your mom at home?” and Telgemeier had drawn herself as a rudimentary stick figure, hollering NO!

Shortly after Telgemeier’s retrospective, “Facing Feelings,” opened in late May, she flew her parents out to Columbus for the public reception. The day before the event, Telgemeier, her parents, a college friend, and I took a tour of the exhibit. On the way to the gallery, we passed a decal of 11-year-old cartoon Raina running full tilt, as if she were dashing up the stairs to see her own show. In the lobby downstairs, dozens of cookies with young Raina’s face on them waited to be handed out at the reception.

In one room of the show, Telgemeier and a curator had assembled a selection from the Raina archives, including pages from her journals, school assignments, and family photos. Telgemeier’s parents lingered here, exclaiming at familiar objects. Her father, Denis, paused at a display of Telgemeier’s most treasured childhood books. “It’s Barefoot Gen !”

Barefoot Gen is a manga series by Keiji Nakazawa based loosely on his experiences as a child in Hiroshima in 1945. Denis had given Telgemeier his copy of the first volume when she was 9, and she zoomed through it on a camping trip, totally absorbed. The comic is unsparing about the details of World War II in Japan: It shows poverty and violence and people ending their own lives to escape their circumstances. Still, Telgemeier was caught off guard when the bomb dropped about 30 pages before the end and nearly every character (except for Gen, his pregnant mother, and a handful of others) was killed. The illustration of the mushroom cloud is chilling; in the aftermath, Gen watches people’s flesh melt off their bones. This was Telgemeier’s first exposure to the depths of human cruelty and suffering. She cried and cried for days, and later made anti-war posters that she pasted all over school.

In her 20s, Telgemeier drew about her experience reading Barefoot Gen in Take-Out ; the issue was on display at the museum. Young Raina runs out to her parents, wailing, “They all DIE!” A few frames later, it’s evening and Raina is looking up at the stars miserably. “I think that book ruined my life,” she says. “And I mean, jeez—it was just a comic book.” A speech balloon enters from out of frame, her mother’s voice: “Raina, there’s no such thing as ‘just a comic book.’ ”

I looked at the text Telgemeier had written for this display. This, she wrote, “has sort of become my career philosophy. Art is important and comics are important. So is sitting with anxiety, discomfort, and confusion, hopefully in the presence of caring individuals!”

Telgemeier had intended for her next book to be about Barefoot Gen and her twin childhood epiphanies that the world can be truly awful and that art can be a meaningful intervention in that awfulness. She drafted the manuscript, but her editors at Scholastic suggested that it needed serious edits. The material was heavier, darker, and more political than her previous work, and could be too risky, given the politically volatile climate of children’s publishing. What’s more, the manuscript told a story that extended beyond Raina’s childhood into Telgemeier’s adult life as an artist—would readers want that? Telgemeier agreed to put the manuscript in a drawer for a little while.

When we talked about this in California, I pushed her on the decision. Just because she has become known writing books for young children, is she obligated to write for that demographic forever? Might not her material age as her readers age?

“Middle grade has been where my sensibilities sell the best,” she said, looking conflicted. “But the question is: If I write another book that’s about older people, but it’s still drawn in my art style, is that going to alienate my readers? Is that going to confuse them, or are they going to be out of their depth? Are they going to be upset by the kinds of things, like the subject matter, that I’m writing about?”

The truth is, little kids read her books no matter how they’re labeled, she pointed out to me—they pick them up from older siblings, or they simply grab them because they recognize her name. This requires care: She posts only PG-rated content on social media, and she never speaks in interviews in a way not suited for kids as young as 5. Maybe, she admitted, it would be too far outside her brand to let young Raina become grown-up Raina. (Even the benign crushes featured in Drama have caused controversy; the book is frequently banned and targeted by conservative activists for its depiction of LGBTQ characters.) Still, she hasn’t given up on the Barefoot Gen project.

As she spoke, I was thinking of a friend of mine whose 7-year-old had just learned from someone else at school about the climate crisis and now can’t sleep through the night. And about another friend whose kid can’t stop worrying about an active shooter coming to school. Telgemeier had read Barefoot Gen at age 9. What do we know about what kids can handle? Or what they are already handling?

On the day of the museum event, I floated around the lobby, interviewing the kids who looked especially rapturous. “What do you like about Raina books?” I asked Cassie, the 8-year-old from Philadelphia. She paused for a second, then smiled sheepishly. “I like everything about them. They’re funny and, like, I’ve been through a lot of the stuff that she’s been through … A bunch of the stuff in Guts—like the anxiety and needing therapy.” She spoke so softly that I had to bend down to hear her.

“What did it feel like when you read Guts for the first time?” I asked.

“Like I finally fitted in. Like there was someone else in the world who felt like me.”

“This is a big splurge for us to make a trip,” Cassie’s mom said. “But I got the tickets, and I didn’t tell her about it until a couple weeks ago. She was like, ‘We’re going on an airplane?!’ She’s never been on an airplane.”

A 16-year-old named Charlotte told me that she’d experienced a really terrible period of anxiety a few years back, and Guts was the first time she’d understood that she wasn’t alone. “I didn’t think anyone else got it,” she said. Her mother, standing next to her, started crying. “She was going through some really deep stuff, and then Guts hit,” she said. “I remember taking the book into her therapist and being like, ‘This. It puts words to what we’re going through.’ Nobody was talking about that. ”

One of the primary emotions expressed in Telgemeier’s memoirs is loneliness—young Raina feels like she’s all by herself with her anxiety, her embarrassments, her jammed teeth. Sue told me that though there are scenes in the books of Raina confessing her fears to her mother, the real Raina didn’t tell her parents much of what was going on—they learned the extent of her struggles only later, when they read her books.

Scott McCloud writes in Understanding Comics that comics are often defined by what they leave out—by the gap left between the lines and shapes on the page and the full, detailed reality that the reader creates with their imagination. The more realistic particulars you add in drawing a face, the more that face is understood by the reader as a specific individual; the more detail you omit, the more that face takes on the quality of an avatar—allowing the reader’s mind to bridge the gap with its own associations and ideas and subjectivity. Young Raina—with her large, oval eyes; dashed-off nose; and single-line eyebrows—has plenty of personality while remaining a relatively neutral protagonist in whom kids can see themselves.

Hers is a different model of courage to hold up for children, though superheroic in its own right. In Guts, when Raina is in the middle of the pea-green panic attack, alone in what seems like an enormous, dark well, she tells her therapist that she feels frozen, unable to move or think or talk, to express herself at all. “When I’m in this space, I feel like I can’t get out,” she says. “I feel like I won’t survive it.”

Her therapist’s response is simple: “Try.”

“I feel like I can’t even try,” Raina protests.

“Try anyway.”

So she tries. The page shows Raina falling through a green-and-black dark space headfirst. In the next panel, we see her sitting—presumably on the therapist’s couch, gripping its edges—but the waves of panic are so intense and she’s hyperventilating so hard that everything else around her is obliterated.

“Concentrate on your feet. Touching the floor.”

Slowly, slowly, Raina’s breathing begins to ease. She is willing to try, and it is horrible, but she survives. The next thing her therapist does is telling: She asks if Raina would find it helpful to explain to other people what she’s going through.

At the end of Guts, Raina hasn’t cured herself of her phobias, but she’s found more foods she can eat without fear. She’s worked up the nerve to tell her friends that she goes to therapy and been surprised to learn that other people go too. She’s not so weird after all. She redoes an oral presentation—one she was too anxious to complete on her first try—and this time makes it a lesson on anxiety, teaching her classmates some of the techniques she’s learned for calming down. In other words, she’s connected and happier—trying, not perfect.

This concept of being bravely in progress still resonates for Telgemeier. She is only in her 40s—young for a retrospective, and too young to speak with certainty about the arc of her own story. When I asked her, on the day of the reception, how she thinks about the bigger picture, she laughed, looking overwhelmed again.

Writing beyond the middle-grade demographic, if it’s something she wants to do, won’t be simple. “I feel like I want to spread my wings in different directions, but I’ve sort of created a box for myself. The industry, the market, whatever—they’re really good with where I am,” Telgemeier had told me when I visited her at the cozy nerd house. “I’m trying to push; I’m trying to expand … But it’s been tricky to land on just the right thing.” Still, tricky doesn’t mean it’s not worth trying. She’d have a better sense of it all, once she went home and had time to reflect. She’d draw her way through it.

This article appears in the March 2024 print edition with the headline “Raina Telgemeier Gets It.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.