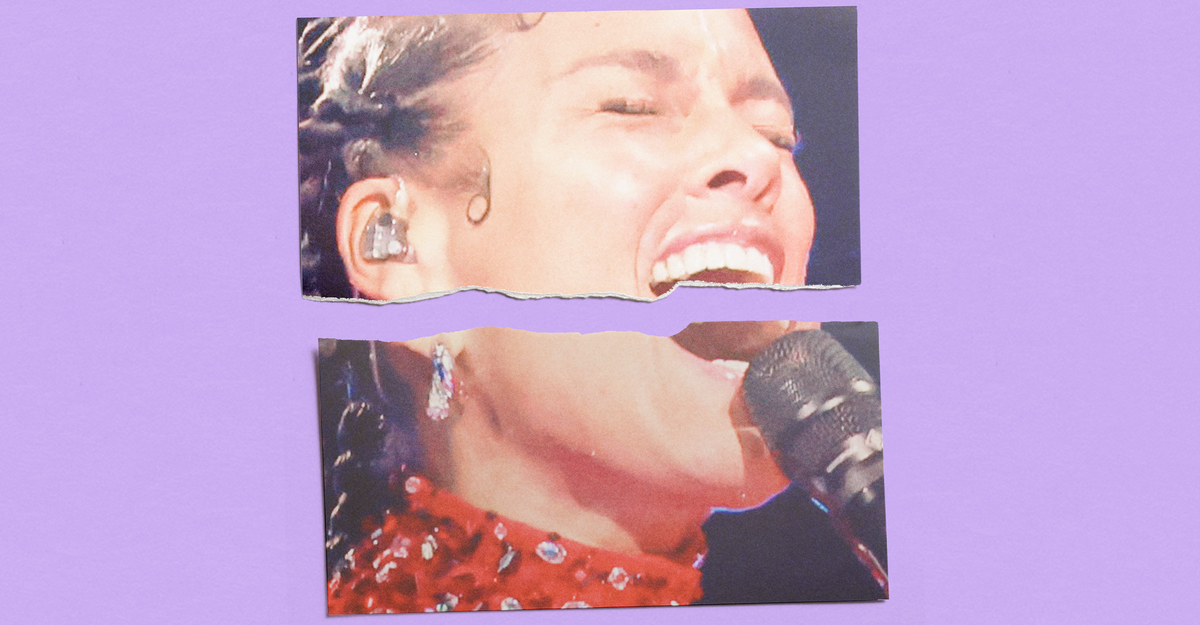

Almost one-third of the way through Usher’s performance at this year’s Super Bowl halftime show, Alicia Keys appeared, attached to a billowing red cape and seated at a matching piano. As the Grammys-festooned pop and R&B singer-songwriter gently played the opening arpeggios of one of her biggest hits, 2004’s “If I Ain’t Got You,” something small but unexpected happened. Instead of easing into the song with the first verse, Keys skipped straight to the chorus—and right on the dramatic opening note, her famously velvety-smooth singing voice noticeably cracked.

In the immediate aftermath, viewers were strikingly quick to pounce on Keys—in the press as well as on social media—for her perceived vocal transgression. Adding to the furor, the sound of Keys’s voice cracking was edited out in the official video uploaded by the NFL. An otherwise-fleeting memory had seemingly fallen prey to pop music’s version of the Mandela effect (a phenomenon where people collectively misremember events). And, as a result, Keys’s performance became a lightning rod for casual music critics and prophets of technological dystopia alike.

Talk to professional singers or voice teachers, though, and any glitches or postproduction fixes are less remarkable than the fact that, unlike so many Super Bowl halftime performers, Keys dared to do it live in the first place (rather than simply lip-synch). The human voice was the only instrument on the stage that could not be replaced with backup equipment in case of failure, and it’s susceptible to dry desert air, smoke machines, and other environmental hazards of performing a pop concert at a Las Vegas football stadium. There’s also the general unpredictability of putting enormous muscle pressure on the vocal cords, which are just thumbnail-size folds of tissue inside the larynx. If a live performer reliable enough to be the singing, piano-playing host of two consecutive Grammys ceremonies could falter on the world’s biggest stage, it’s worth contemplating why so many lesser mortals attempt to raise their voices in song at all—and the thrilling rewards that come with turning in a flawless performance.

The style of singing that has been prevalent in pop music ever since rock and roll—the booming, belting, and, yes, often yelling that succeeded the dulcet tones of traditional confections such as “(How Much Is) That Doggy in the Window?”—is almost inevitably unkind to vocal cords. Just ask Miley Cyrus, who has been admirably open about how decades of touring damaged her voice, or Jon Bon Jovi, who at 61 is recovering from a career-threatening throat ailment. Singers including Adele and Snail Mail’s Lindsey Jordan have undergone vocal-cord surgery; Celine Dion famously didn’t speak when she was on tour. Keys herself canceled shows in 2008, near the peak of her popularity on the charts, because of swollen vocal cords.

Michael Dean, a voice-performance professor at UCLA who has seen Keys perform “many times,” draws a parallel to ballet, an art form that by its very nature destroys dancers’ feet. “Opera singers and jazz singers, to a certain extent, use breath pressure to make their sounds, which is just fine for the voice,” Dean says, referring to the sort of airflow techniques that allow, say, a prima donna to be heard without amplification over an orchestra. Pop, R&B, and rock singers, he says, use “muscle pressure” to push louder and higher: “It is inherently injurious to the voice to do that.” Vocal cords can generate nearly limitless varieties of sounds, but they can take only so much strain. (Steroid shots are one option for reducing inflammation, although they are best used in moderation due to long-term side effects.)

Pop vocals, then, routinely run up against the physical limits of the human body. Yet what makes a song difficult to sing doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with having to hit a particularly tricky note. “It’s not the song range,” Anne Peckham, the chair of the voice department at Berklee College of Music, told me. “It’s the power and volume that is used to make an emotional impact. When you’re singing with that kind of power, sometimes the voice just says, I’m not quite ready for that.” Geoff Rickly of the post-hardcore band Thursday told me he feels Keys’s pain, having experienced vocal issues before a performance, more than 20 years ago, on Late Night With Conan O’Brien—a huge opportunity that didn’t go as well as he’d hoped for. Right now his voice is worn-out just in time for a succession of financially unskippable tour dates. “It’s usually the note you use the most that goes out first,” Rickly explained. “A good singer like [Keys] doesn’t miss the note. She goes for the note, and her voice just won’t. Your vocal cords paralyze for a second.”

That said, some songs are still more difficult than others, and “If I Ain’t Got You” isn’t easy. Inès Nassara, a singer-songwriter and an actor based in Brooklyn, told me that there are some tunes where she can coast, but for Keys’s song, “I just have to think about my training more.” Psychology matters too: Nassara remembers one time when she had to sing Whitney Houston’s “I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me)” for an audition but was sick that day. “Singing is so mental that because of that one day that I didn’t really nail it, it’s been hard for me to sing it ever since,” she said. Other numbers that have challenged her over the course of three-hour gigs as a wedding singer include Bon Jovi’s “Livin’ on a Prayer”—“It just gets really high even for a femme voice”—and various hits by lofty-voiced male singers such as Stevie Wonder, Bruno Mars, and Justin Timberlake. “If you don’t pace yourself, the night can get really long.”

Of course, it’s not only trained singers who take on songs that might give our larynges a fright. Sara Sherr, a former music critic and a Philadelphia karaoke DJ since 2006, says Jennifer Hudson’s version of “And I Am Telling You I’m Not Going” from Dreamgirls and Whitney Houston’s “I Have Nothing” are the songs she has most often heard trip up singers. But for her, the potential for imperfection is part of the point. Karaoke performances are always addressed to a theoretical someone, even if they take place in front of a big crowd—they express feelings that can’t be stated through words alone. “It’s almost more effective if you’re missing half the notes,” Sherr told me. “That’s vulnerability.” When a professional slips up, it’s surprising; when amateurs do, it can be a way of conveying how much they mean what they’re singing.

Singers may choose to make songs easier for themselves, either by changing the notes or by shifting into a lighter register known as a “head voice.” But when you’re telling a story through music, the tightrope drama may be essential to the plot. Viewers might be comfortable opining on vocal performances like an armchair Simon Cowell, but even the biggest breakout stars of TV singing contests, such as Susan Boyle, have their voices crack sometimes. Marlain Angelides, the singer for the “All Girls All Zeppelin” cover band Lez Zeppelin, has been told by a speech therapist that she’s running a marathon with each of her two-hour concerts. But the grit and mess of a singer such as Robert Plant is a reminder of how the human body can sound when unaided by omnipresent digital technology such as Auto-Tune. “When we cry, our voice cracks,” Angelides told me. “When you sing, it’s a heightened version of how we feel. Why not have a crack?” No, Keys’s momentary lapse in Vegas certainly wouldn’t have been ideal from a critic’s standpoint—but it is an ideal example of the vertiginous risk that is at the heart of live pop music.

The singer-songwriter Madi Diaz has misgivings about her own televised performance, on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, on the Friday before the Super Bowl. “Oh God, it wasn’t my strongest,” Diaz told me. As for Keys, Diaz reflected: “Olympians trip, dude. It just happens.” What’s different in 2024, perhaps, is the capacity for a televised gig to instantaneously ricochet across the globe and become a meme. Such a combination of fallibility and hyper-exposure seems like all the more reason to celebrate the enduring and deeply human bravery of live performance. As the late David Berman of the indie-rock band Silver Jews once sang, “All my favorite singers couldn’t sing.”