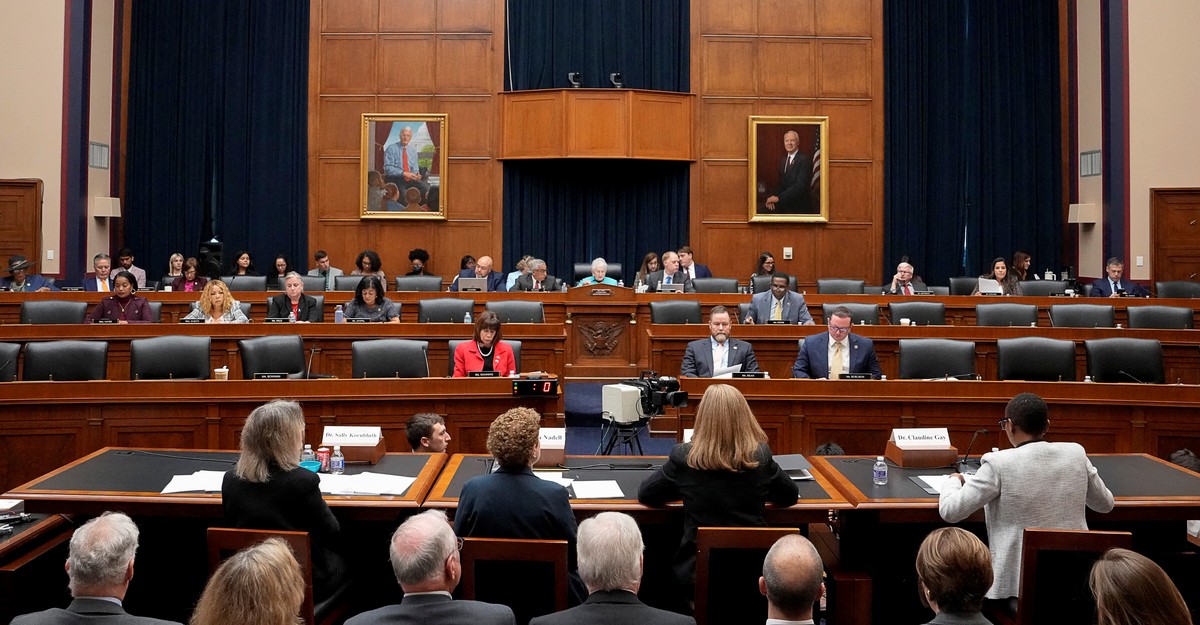

The presidents of Harvard, the University of Pennsylvania, and MIT testified in front of Congress this week. Their performance was a disaster.

The three leaders of these prestigious institutions seemed coached, presumably by a team of lawyers and PR consultants, to give hedging answers, and they doggedly stuck to their talking points. As a result, their responses were robotic, betrayed a lack of empathy, and never made a serious attempt to defend the larger mission that their universities supposedly serve. Throughout the hearing, the three presidents perfectly encapsulated the broader malaise of America’s most elite universities, which excel at avoiding lawsuits and increasing their endowments but seem to have little sense of why they were founded or what justifies the lavish taxpayer subsidies they receive.

The most damaging moments came when the three presidents were asked by Representative Elise Stefanik, Republican of New York, whether “calling for the genocide of Jews” would violate their universities’ policies on free speech. Such a call could be a violation, “if targeted at individuals, not making public statements,” Sally Kornbluth, the president of MIT, said. “If the speech turns into conduct, it can be harassment,” Elizabeth Magill, the president of the University of Pennsylvania, said. “It can be, depending on the context,” Claudine Gay, the president of Harvard, said.

Many people who were rightly horrified by the congressional hearings faulted Kornbluth, Magill, and Gay for refusing to say they would punish students for expressing this kind of abhorrent sentiment. But that is overly simple. In a narrow, technical sense, the three presidents were correct to state that their current policies would probably not penalize offensive political speech. In a more substantive sense, universities should defend a very broad definition of academic freedom, one that shields students and faculty members from punishment for expressing a political opinion, no matter how abhorrent.

The real problem was that none of these university leaders made a clear, coherent case for their institutions’ values. So when they did invoke academic freedom, they came across as insincere or hypocritical—an impression only reinforced by their record of failing to stand up for those on their campus who have come under fire for controversial speech in the past.

When pressed by Stefanik, the presidents kept claiming a supposedly ironclad commitment to free speech as the reason they would not be able to punish calls for a genocide of Jews. But each of their institutions has failed lamentably to protect their own scholars’ free speech—by canceling lectures by visiting academics, pushing out heterodox faculty members, and trying to revoke the tenure of professors who have voiced views far less hateful than advocating genocide.

Universities are now paying the price for those missteps. If they claim to stand for free speech, they must be consistent. What they cannot do is engage in a selective enforcement of rules that effectively gives one form of hatred—namely pro-Hamas and anti-Jewish advocacy—the stamp of university approval while punishing students and faculty members for speech that certainly does not rise to the same standard of hatefulness.

The problems over freedom of expression at American universities long preceded the recent controversies. In October 2021, Dorian Abbot, a renowned climate researcher, was supposed to deliver the prestigious John Carlson Lecture at MIT. But because Abbot had written an article for Newsweek opposing affirmative action, graduate students at the school started a petition to stop Abbot from delivering his speech. The university duly complied.

Until 2021, Carole Hooven was a lecturer on human evolutionary biology at Harvard. When promoting a scholarly book about testosterone, she suggested on national television that there are two biological sexes: male and female. In response, a graduate student who also served as the director of her department’s Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging taskforce denounced Hooven’s remarks as “transphobic and harmful.” Hooven’s colleagues stopped talking with her, administrators failed to defend her, graduate students bullied her. Hooven first took a leave of absence and later left the university altogether.

At the University of Pennsylvania’s law school, Professor Amy Wax has expressed views that many people (including me) find offensive. She has, for example, argued that America should select immigrants based on their cultures of origin, acknowledging that this “means in effect taking the position that our country will be better off with more whites and fewer non-whites.” Even so, nothing she has said remotely comes close to calling for genocide—yet the university has been trying to revoke Wax’s tenure and get her fired for years.

These aren’t isolated incidents; the failure is systemic. According to the free-speech rankings published by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), MIT does relatively poorly, in the middle of the pack at 136th out of 248 assessed universities. The University of Pennsylvania does awfully, in penultimate place at position 247. Harvard beats out stiff competition to come in dead last.

All of this provides crucial context for Tuesday’s embarrassing congressional hearing. The presidents of Harvard, MIT, and UPenn were disingenuous when they claimed that their response to anti-Semitism on campus was hamstrung by a commitment to free speech. Who can doubt that they would have been more forthright in condemning calls for the murder of trans people or the lynching of Black Americans, for example, when their own institutions have disinvited speakers for the crime of opposing affirmative action or have pushed out professors for believing that biological sex is real?

The blowback from the presidents’ disastrous congressional appearance has been so intense that all three, evidently fearing for their jobs, have quickly turned to damage limitation. Harvard published a statement from Gay on X (formerly Twitter) suggesting that her critics had misunderstood her: “Calls for violence or genocide against the Jewish community, or any religious or ethnic group are vile, they have no place at Harvard, and those who threaten our Jewish students will be held to account.”

The University of Pennsylvania released a video message from its president. Changing her answer, Magill now claimed that the language she was asked about in Congress “would be harassment or intimidation.” For decades, she explained, “Penn’s policies have been guided by the Constitution and the law.” But “in today’s world, where we are seeing signs of hate proliferating across our campus and our world in a way not seen in years, these policies need to be clarified and evaluated.” The university, she promised, would immediately start the process of rewriting its rules. (So much for the Constitution and the law.)

Magill could have used this moment to own up to her failures over the course of the past years and recommit herself to her mission. Instead, she is ineptly trying to mollify the public by promising that she will adopt more restrictive rules—effectively going even further in abandoning her university’s commitment to free speech.

As David Frum argued this week, that reflex fundamentally misidentifies the source of the problem. The reason the recent bullying and intimidation of Jewish students have been allowed to continue is not that universities are unable to punish students who engage in harassment. Rather, some of the university presidents who appeared before Congress have failed to discipline students who broke existing rules against disrupting classes, destroying property, and targeting individuals for abuse. MIT, for example, reportedly desisted from punishing foreign-born students for clear violations of student-conduct rules for fear of affecting their visa status.

Stricter codes governing free speech won’t help students from minority groups who don’t enjoy the backing of university administrators in future. We have every reason to expect these officials to continue to apply those laws unevenly, chilling the speech of anybody who offends against campus orthodoxy while giving broad latitude to students who tout popular progressive causes to intimidate their enemies with impunity. As a statement this week from FIRE rightly pointed out, “universities will not enforce a rule against ‘calls for genocide’ in the way elected officials calling for President Magill’s resignation think they will. Dissenting and unpopular speech—whether pro-Israeli or pro-Palestinian, conservative or liberal—will be silenced.”

Instead of overcorrecting for their inability to acknowledge past errors and recommit to protecting free speech, university leaders should follow the advice of those who care about and understand academic freedom. These leaders need to protect those who express a controversial opinion, regardless of what it is; they should punish students for forbidden conduct that disrupts classes or infringes on others’ right to express themselves; and they must get universities out of the business of taking institutional positions on political events.

Reflecting on her departure from Harvard, Hooven had helpful advice for how others could avoid her fate:

To begin with, university leaders must be encouraged to develop a moral compass, integrity, and a backbone—admittedly, this is often a tough order. Second, the university’s position on academic freedom must be frequently trumpeted. Third, administrators should never weigh in on the accuracy of controversial or offensive claims—doing so signals that views that fail the purity test are less likely to be protected. And finally, university leadership must frequently remind the campus community that the foremost mission of a university is the pursuit, preservation, and dissemination of knowledge. This cannot happen without academic freedom.