This is Work in Progress, a newsletter about work, technology, and how to solve some of America’s biggest problems. Sign up here.

You’re at home on a work night. Your partner had a brutal day and needs to vent.

“My boss was a jerk,” your partner says, “and I feel like none of my colleagues like me.”

“I have an idea,” you respond. “Maybe you should organize a happy hour to clear the air.”

“You’re not listening. My boss is just a jerk, plain and simple. I’ve tried being nice, and it’s impossible with her. Nobody in the office gets this kind of treatment.”

“I hear you. I’m just trying to help. And if you organize that happy hour, you might—”

“Stop trying to help me fix the problem and please just listen to me,” your partner says. And now it’s your turn to get upset. Because you are listening, you think. To every word! Isn’t that what good partners do? And somehow, all you’ve done is start a fight.

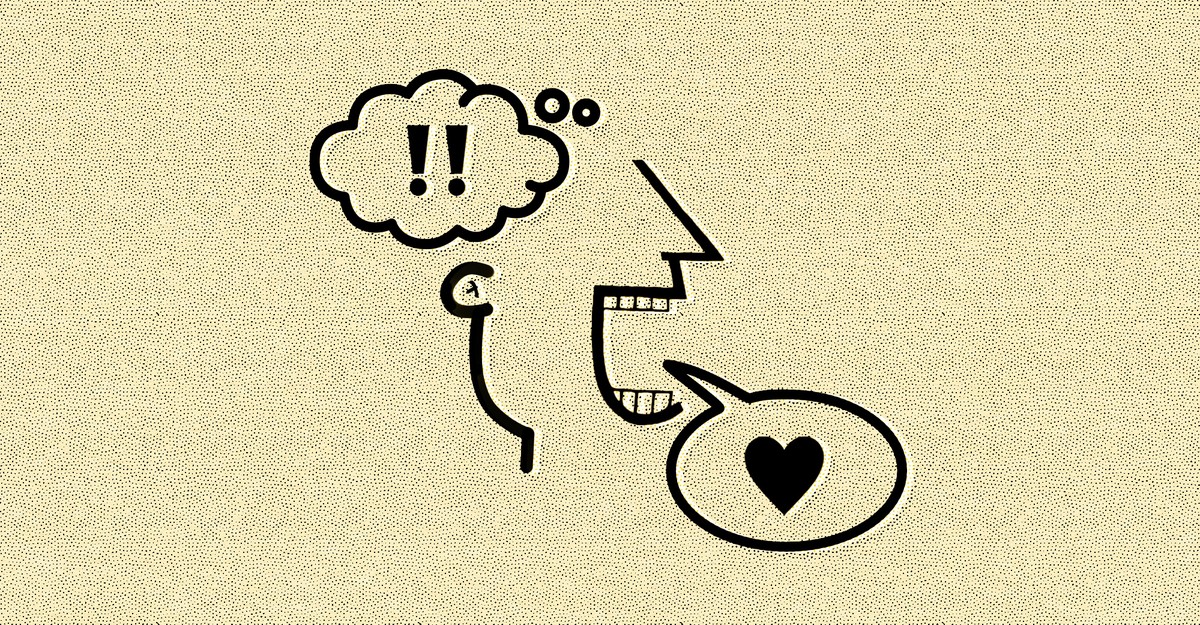

In his new book, Supercommunicators, the journalist Charles Duhigg writes that one of the most common sources of conflicts in relationships is when partners don’t agree on the type of conversation they’re having. Some conversations are practical: Let’s solve a problem together. Others are emotional: Let’s talk about and understand our feelings. Many fights mistake practical for emotional conversations, and vice versa.

In the above scenario, the first partner wanted to share her emotions and have them confirmed and validated. The second partner skipped right over the emotional part and moved immediately to drawing up a list of solutions. The resulting conflict wasn’t about a lack of love or care. The second partner simply didn’t have the perspective to stand back and see the shape of the conversation: This isn’t a problem-solving brainstorm; this is a vent session.

One might assume that the best conversationalists are the quickest with words, or the most talented at constructing arguments, or the most clever at asking questions to glean novel information. But Duhigg says none of that is really core to the art of hard conversations in relationships. Far more important is knowing the difference between an emotional exchange and a practical one.

In the 1970s, a group of psychologists from across the country wanted to understand how married people navigate conflicts. Known as the “Love Shrinks,” they videotaped interviews of husbands and wives talking about practically everything: chores, kids, friends, sex. The videos captured more than 1,000 arguments.

When the psychologists coded the data, two things became obvious. First, all couples fight. Second, fights have wildly different effects on different couples. The psychologists wanted to understand why, for some couples, fights are a poison that destroys their relationship dose by dose, whereas for others, fights are more like a physical-therapy session—painful in the moment but strengthening bonds over time.

While writing Supercommunicators, Duhigg spoke with several of the Love Shrinks and read the fight transcripts. Duhigg told me on an episode of my podcast, Plain English, that despite the psychologists’ expertise, all of their initial hypotheses about fighting were wrong.

The first hypothesis was that happy and unhappy couples fight about different things. Perhaps, they assumed, unhappy people fight over the big stuff—money, health, substance abuse—and happy couples merely squabble over trivial items (“You never put the broom back!”) that won’t leave a dent. That hypothesis was wrong. If you and your partner have fights over weighty topics such as responsibility, money, and child-rearing, have no fear: So does everyone else.

Hypothesis No. 2: Happy couples are just more resilient. Maybe good couples are just better at forgiving and forgetting. Wrong again, Duhigg said. In fact, the researchers found that many happy couples were terrible at forgiving and forgetting. They had the same fight over and over again, like Sisyphus pushing the same boulder up the same hill. But, heeding the advice of Camus, these Sisyphean couples still imagined themselves as happy.

The key, Duhigg writes, isn’t that happy couples fight over the right things. Happy couples fight in the right way.“What they found was that in bad conversations and bad fights, both people in the relationship were trying to control each other,” Duhigg said. This can take the form of you need to statements: “You need to stop talking,” “And you need to stop working so much,” “Well, you need to work more,” “Well, you need to talk to me more,” “Well, you need to listen to me more!”

Rather than try to control their partners, happy couples were more likely to focus on controlling themselves. They sat with silence more. They slowed down fights by reflecting before talking. They leaned on I statements (“I feel hurt that you’d say that about my parents”) rather than assumptive ones (“You’ve always just hated my mother”). Healthy couples also tried to control the boundaries of the conflict itself. “Happy couples, when they fight, usually try to make the fight as small as possible, not let it bleed into other fights,” Benjamin Karney, who helps direct the Marriage and Close Relationships Lab at UCLA, told Duhigg.

Karney’s quote appears on page 153 of my copy of Supercommunicators. I know this because the page is sharply dog-eared and compulsively underlined, and various passages are circled and starred. When I read this section, my eyes bugged with the shock of recognition. This is—or, I’d like to think, was—me.

Several years ago, I noticed that when I felt defensive in a fight, I would always change the subject without realizing it. For example, my wife might ask me to respond to her calls or texts more promptly. Rather than say “You’re right; I’ll text back faster” or propose a reasonable cadence for text messaging, I would start with a simple defense such as “I was busy,” which might lead to “And why can’t you see how hard I work?,” which might set me up for a monologue about some unresolved conflict from several weeks ago.

Over time, this ridiculous behavior became so glaringly obvious to me that I came up with a phrase for it: I was “opening new tabs.” My wife had raised a single issue, like opening a single tab on a browser. Rather than engage with that request, I mashed “Control-T” over and over again to fill the conversation browser with related tabs. A “Respect my schedule” tab. A “Show you respect me too” tab. A “Remember that totally unrelated fight from three weeks ago? No? Well, I have it memorized, and I’m going to recite it back to you” tab. Just as too many tabs can slow down processing and crash the browser, too many conversation tabs inevitably delay mutual understanding and crash a productive dialogue.

As our relationship progressed, “Don’t open new tabs!” became a catchphrase in hard conversations. The idea was, if one partner feels frustrated that the other didn’t do the dishes, don’t bring up the previous fight (tab two!), and don’t bring up a new fight (tab three!). Restrict the conversation to soap and plates.

“Don’t open new tabs” isn’t some utterly novel insight. It’s the flip side of what relationships psychologists call kitchen-sinking. As Duhigg explained to me, the key to a good fight is exerting control over both ourselves and the topic of conversation.

Practically speaking, my talk with Duhigg convinced me that many relationships could benefit from asking three very brief questions in the heat of a conflict.

- “Are we opening new tabs?” Too many fights happen when one hard conversation branches into several hard conversations.

- “Are we venting or problem-solving?” Too many fights happen when one partner tries to have an emotional conversation and feels shut down by a barrage of unemotional practical suggestions.

- “What if I tried to control only myself?” Many fights are exacerbated by you need to statements. I need to statements direct inward the urge to control.

The goal, Duhigg reminded me, isn’t to avoid conflict. It’s to recognize, at the highest level, what kind of conversation you’re actually having.